Photo Credit: Antara Mrinal

Clear Cut Livelihood Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Sep 13, 2025 11:16 IST

Written By: Antara Mrinal

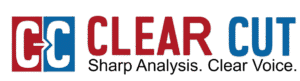

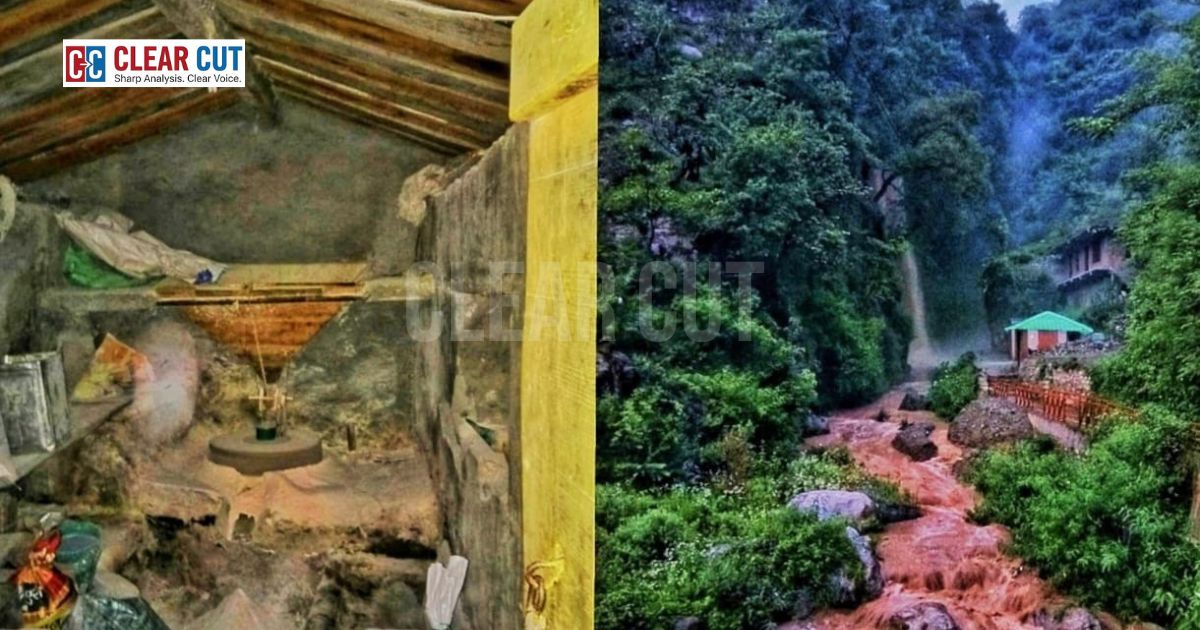

On a brisk morning in Chakrata, a town in Uttarakhand, the answer to the sound of raindrops falling is the thumping of wooden cogs amidst the flow of a rushing river. In a humble stone structure that has stood for centuries beside the stream, an ancient machine is grinding grain into flour without electricity, no diesel, and no form of modern fuel. This is the Gharat (pronounced as gharāt), the traditional Himalayan watermill. For centuries gharats have transformed streams into livelihoods, feeding families and tying communities together. In a world of turbines and megawatts, gharats present a unique opportunity to explore the intersection of tradition and innovation.

What exactly is a Gharat?

A gharat is a traditional watermill, or hydraulic mill, prevalent in the Himalayas, in the states of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, as well as parts of the Northeast. They are made from local stone, timber, and mud, and normally consist of 2 small rooms – one with the grinder stones, and one with the turbine which is powered by water. The gharat functions imbued with a historically simple yet ingenious architecture. Water is diverted through a nearby stream through a channel referred to as a gool or kuhl. The culvert concentrates water to a turbine, and because of that limitation, the water is delivered with velocity that drives the turbine to rotate horizontally. The horizontal motion of the turbine is delivered to a vertical shaft along with the spindles connecting it to the upper stone of the mill. As the upper stone turns against the fixed lower stone, grain continuously enters between the two stones and gets ground into flour. Scholars have studied and reported how gharats are an important, inexpensive, and existed as one of the more eco-friendly livelihood opportunities, made from locally available materials, and kitchen stoves, with a little outside assistance.

Photo Credit: Rajender Bisht

How Weather and Climate Shape Their Efficiency

The efficiency of gharats is linked to how the water comes through seasonally. In the summer and monsoon, the streams are swollen, and gharats have strong continuous flow and can run almost all the time. Villagers will wait in line overnight during harvest season and bring them sacks of wheat, maize, or millet. But in the winter, it all changes. In the winter in the higher Himalayas, as snow covers the ground and streams become barely a trickle, many gharats remain quiet, and they must wait for the spring melt before beginning to work again. Climate change seems to be pushing this into a new area of uncertainty. The retreat of glaciers, unpredictable rainfall, and flash floods have kept variance in normal water flow that used to be regular.

Voices from the Hills

For Himalayan communities, gharats are much more than machines; they are vital links to a tradition and mutual trust. Ramesh Rawat, a gharati from Uttarkashi, notes that his mill was constructed by his grandfather and had served the village for generations. Payment is rarely made in the form of cash, rather, he keeps just a small portion of the flour for himself, as payment. Ramesh states that the gharat is not a means of making a living, but an inheritance, and a connection to the village. Women remember how these watermills lifted a significant burden from their lives. Kamla Devi of Pauri says her grandmother often told her how relieved she was to no longer hold the burden of grinding grain by hand, as it took up so many hours of exhausting labor. The younger generation says something different. Twenty-two-year-old Neeraj states that people prefer store-bought flour, as it is faster and seen as cleaner. Now, his family’s gharat sits unused, quarrying tools covered in dust, even though the water still runs nearby. These voices reflect the tensions of tradition and modernity in the mountains.

The Significance of Hydro-Energy in the Hills

Often referred to as the lifelines of India, the Himalayan Rivers provide water, food, and energy to millions of people. While the energy sector is dominated by large hydropower projects, there are high ecological and social costs associated with them, generating landslides, displacement, disruption of habitats, to name but a few. Gharats, however, have demonstrated how hydro-energy can be generated at a far smaller scale with much lower ecological costs, and can be more sustainable. Research has documented how gharats can transition from their current purpose, grinding grain, through relatively uncomplicated modifications – like improving hydro turbines and channels, to generating mechanical energy that can be converted to generate electricity. Micro-hydropower systems can generate enough energy to power households, charge phones, and power radios in rural areas. Recently, pilot projects funded and initiated by agencies, such as the French Development Agency (AFD), have also been trying to convert traditional gharats to hybrid units, acting as both flour mills and micro-hydro power plants. The traditional gharats of the Himalayan region gesture toward a future where gharats serve the function of complementing large dams by providing distributed, low-risk renewable energy.

Why Gharats Still Matter

Gharats are significant because they exemplify sustainability in the truest sense. They run on renewable water flow, produce no greenhouse gases and consume no fossil fuels. They are made from local materials, operated by the villagers themselves, cost-effective and durable. They represent affordable flour and less manual burden for people, therefore supporting food security and local economy. Gharats go beyond their perceived value and are cultural icons which maintain history and identities of each associated community. Gharats which have been fitted with modern equipment serve as multi-purpose systems operating machines which produce electricity, compress oil, extract oil, and/or direct a small agro-processing unit. These modernized gharats represent possible future systems which further realized energy independence in villages that are quite far from a stable grid system.

Challenges on the Path

Simultaneously, gharats endure serious challenges to their sustainability. They are limited to only being relied on during particular seasons, especially when dry winters are in season as gharats may not function properly. Climate change also continues to affect the very streams that are crucial for keeping gharats running as flash flooding destroys both the channels and the turbines. Additionally, in towns, the availability of cheap and easy-to-access flour has grounded demand for gharats. The result has caused many gharats to remain abandoned and neglected. Gharats also lack innovative technology, which has rendered them less productive than comparable modern mills. Hodges (2017) notes that the policies often used by the government, tend to overlook gharats and prioritize supports policies toward large hydropower systems and central stations rather than on community solutions. Gharats will risk becoming entirely neglected or forgotten if they do not receive the same attention and support as existing comparable systems.

A Bridge Between Past and Future

The fate of Himalayan gharats hinges on whether they become archaic notions or guides to sustainable livelihoods. Picture this: a village where a modernized gharat grinds flour during the day and runs LED lamps at night; a village whose farmers use the energy to refrigerate vegetables and operate small workshops. This is certainly possible since pilot projects from Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand indicate it is achievable. Universities and government, along with NGOs and local communities, must unite to re-establish gharats with technology but maintain cultural legitimacy. As we battle climate disasters and energy inequities, these watermills offer an unadorned potential.

Closing Thought

As the night settles over mountain villages, the gharat hums above the tumbling stream, grain becomes flour, tradition becomes food and water becomes strength. Gharats are not technologies, they are philosophies in wood and stone teaching balance, resilience and respect for the natural world. The question is not whether gharats are relevant in a progressive world but rather, can we afford to lose the harmony with nature that they represent?