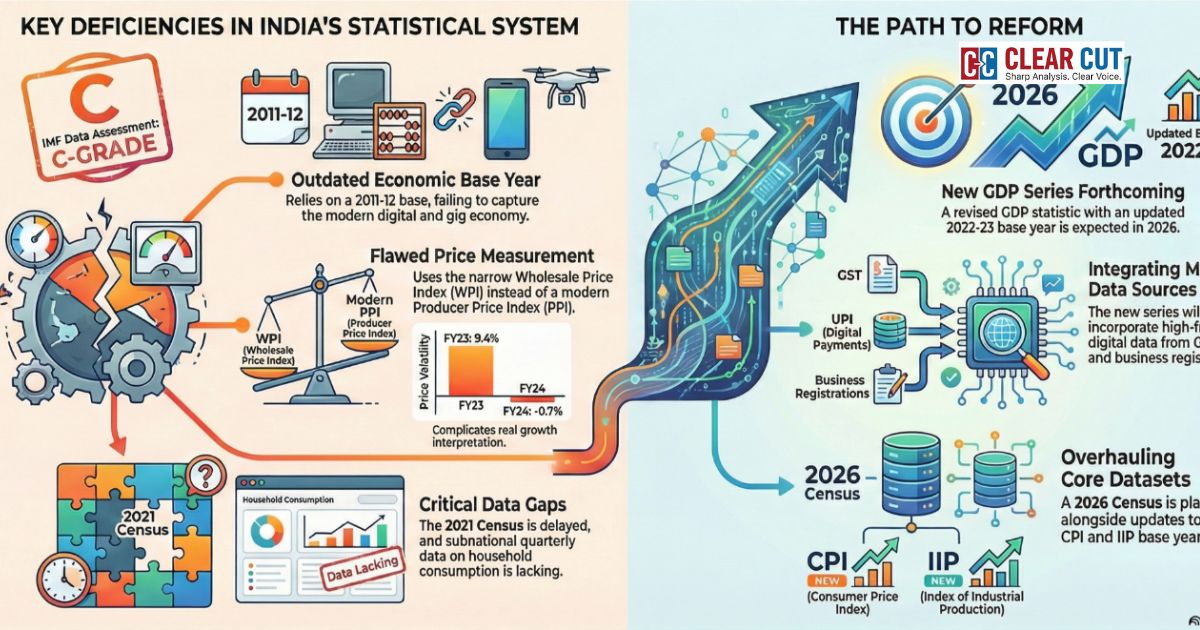

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) 2025 Staff Report on India reignited discussion about the nation’s statistical architecture. It rated India’s national accounts data a C-grade. It stated that the evaluation of national accounts has numerous deficiencies. It has drawn attention from around the world. Whereas other macroeconomic datasets obtained a general satisfactory B-grade. The grade indicates methodological flaws, out-of-date base years, inconsistent macro indicators and substantial delays in fiscal consolidation. It rather didn’t point to a lack of data. Such shortcomings affect investor confidence, policy evaluation and the legitimacy of macroeconomic management from the standpoint of international surveillance.

Base Year Obsolescence and Its Implications#

India’s persistent reliance on the 2011-12 base year for GDP and GVA estimation is one of the main issues raised by the IMF. India’s economy has undergone significant change during the past ten years. The older base year is no longer enough to capture current economic realities due to the increase of digital services, fintech, the gig economy, changes in manufacturing mix, and changes in consumption habits. Base-year updates are crucial for integrating new administrative datasets as well as for accounting for changes in economic structure. National income estimates run the danger of overstating or understating growth in the absence of such revisions, making them difficult to compare with international statistical standards.

Missed Opportunities for Data Integration#

Information like GST reports, UPI transactions, and MCA-21 company forms could be integrated with a more recent base year. Unprecedented real-time view into economic activity is provided by these high-frequency, digital administrative sources. Their removal weakens the timely updates of national accounts and increases estimation error by sustained reliance on traditional surveys and proxies.

Price Indices and the Deflator Challenge: Dependence on the Wholesale Price Index#

The ongoing use of the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) in place of a thorough Producer Price Index (PPI) is another major problem. The WPI is a poor instrument for recording price changes at the producer level due to its narrow coverage of the value chain. The IMF points out that relying on the WPI for deflation creates biases into actual production measurement. In an economy where industrial structures, supply chains and input compositions have undergone significant changes this is crucial.

Volatility in Price Movements#

The GDP deflator is significantly impacted by changes in the WPI and CPI as per recent patterns. The WPI inflation fluctuated from 9.4% in FY23 to -0.7% in FY24 before reverting to deflation in 2025. While retail inflation dropped to 1.9% in October FY26. Real growth interpretation is made more difficult by this volatility. Nominal expansions may not always signify increased output if price movements are erratic. Differentiating actual economic performance becomes analytically vulnerable in the absence of a strong PPI framework.

Methodological Gaps in National Accounts#

A major methodological limitation is India’s continued use of single deflation rather than the internationally accepted double-deflation method. Double deflation employs separate deflators for inputs and outputs. It produces more accurate GVA estimates. In its absence, productivity and value addition calculations particularly in manufacturing and services may be significantly biased. This undermines assessment of structural transformation, sectoral performance and comparative competitiveness.

Production- Expenditure GDP Discrepancies#

Additionally, the IMF highlights discrepancies between GDP estimates from the production and expenditure sides. Unorganized manufacturing, informal service activities and rare household consumption surveys are the main causes of these disparities. Measurement is made more difficult by India’s sizable informal sector. The estimation issue is made worse by huge survey delays. Evaluations of the effects of poverty, inequality and welfare remain speculative in the absence of timely consumer and employment statistics.

Fiscal Data Limitations and the timely updates issues#

The IMF’s study draws attention to ongoing delays in the central government’s and the states’ collection of consolidated budgetary statistics. Evaluating debt sustainability, revenue buoyancy and countercyclical policy space all depend on timely fiscal consolidation.

The significance of timely reporting is highlighted by recent revenue trends. The gross tax revenue increase for April-September FY26 fell sharply to 2.84% from over 12% in the prior year. Income tax and GST collection weaknesses reflect larger macroeconomic issues. The ability to assess the accuracy of GVA estimates partially is dependent on tax revenue patterns. It is hampered when fiscal data is delayed.

Demographic and Subnational Data Gaps Census Delay and Its Consequences#

India is still dependent on population estimates from the 2011 Census. The 2021 Census is still pending. Such a long time between enumerations has a direct impact on labour force estimates, welfare targeting, urban-rural planning and per-capita measures in a society. Errors in demographics have a cascading effect on macroeconomic metrics. It can hamper sectoral productivity and unemployment rates.

Limited Quarterly State-Level Data#

There is still a dearth of quarterly data on household consumption, savings, investment and GDP at the state level. Targeted fiscal transfers and evidence-based regional planning are hampered by the lack of detailed subnational data. This in turn arises due to India’s extreme regional heterogeneity. It limits scholars’ ability to compare different states. It also limits their understanding of the geography of growth.

Grade Reflective of the Real Economy#

The IMF’s C-grade is not seen by many academics as a sign of more serious economic deterioration. India’s median statistical grade of B is comparable to that of similar economies like South Africa and China. Moreover, the IMF itself projects robust economic performance. It predicts GDP estimated to grow at 6.6 per cent in FY26 despite external headwinds and tariff pressures. This implies that technical issues rather than macroeconomic fragility are reflected in the rating.

Reforms to Strengthen Statistical Credibility#

Significant statistical reforms are being pursued by the Indian government. Expected in 2026, a revised GDP statistic with a base year of 2022–2023 will incorporate business registrations, UPI and GST. Important modernisation efforts include the planned 2026 Census, extension of PPI coverage for manufactured items and updating of CPI and IIP base years. These improvements seek to increase precision, coherence and global alignment.

Conclusion#

It is important to view the IMF’s assessment as both an opportunity and a critique. Statistical credibility is essential for policymaking, international financial trust and educated public discourse. This is especially crucial in an economy as large and ambitious as India’s. India can create a stronger and more transparent statistical environment by filling in data gaps. It can be addressed in base-year, price measurement, coverage of the informal sector and fiscal consolidation. India’s long-term growth trajectory is firmly entrenched in the 7-8% range. If supported by strengthening the architecture of national accounts, it may also increase international credibility.

Clear Cut Research Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Dec 09, 2025 05:20 IST

Written By: Nidhi Chandrikapure