Children are frequently hailed as a country’s future symbols of growth, hope, and continuity. Millions of

children in India suffer from dangers to their safety, dignity and well-being, which contrasts sharply with this idealised image. Children continue to be among the most vulnerable groups in Indian society. Despite constitutional protections and progressive laws, especially when it comes to crimes involving sexual abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and violence. The crux of India’s current child protection problem is this paradox between the promise of childhood and the ongoing failure to protect it.

The POCSO Act, 2012, is a significant piece of legislation that addresses sexual offences against children using a framework that is both gender-neutral and child-centric. To expedite justice, the Act established strict penalties, child-friendly investigation and trial processes, mandated reporting, and specialised courts. However, even after over ten years of deployment, concerns about its practical efficacy persist. The goals of the law are nonetheless undermined by low conviction rates, drawn-out trial times, poor infrastructure, a shortage of qualified staff, and the secondary victimisation of children.

This section of policy analysis uses an examination of significant case laws to critically assess the goals, procedures, and court interpretation of the POCSO Act. It also aims to identify global best practices that can inform legislative reforms and enhance enforcement mechanisms by situating India’s child protection framework within a comparative international context. By arguing that child protection is not only a legal requirement but also a moral and social imperative essential to India’s democratic and developmental goals, the analysis adds to the larger conver sation on protecting childhood.

POCSO Act, 2012: Meaning, Scope, and Historical Context#

When the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012, was adopted, India was experiencing a dramatic increase in crimes against children. Prior to this statute, there was no

single national law that addressed sexual offenses against minors. The Indian Penal Code’s general sections, which were not intended to acknowledge children’s vulnerability, were used to manage such

cases. This was altered by the POCSO Act. It established a precise legal framework to shield all children under the age of eighteen from exploitation, sexual abuse, and harassment. The law establishes

child-friendly reporting, investigation, and trial procedures, is gender-neutral, and imposes severe penalties.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, research and criminal statistics showed widespread child sexual abuse and substantial under child sexual abuse and substantial underreporting, which made POCSO necessary.

Many cases remained unreported because of social stigma, fear, and the lack of child-sensitive systems. There were significant gaps in protection since non-penetrative abuse and child pornography were not recognized as separate.

The necessity of reform was further emphasized by India’s 1992 adherence to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. A specific child protection statute has been regularly demanded by courts, civil society organizations, and the statute Commission. The POCSO Act, which was passed in 2012 as a result of these

efforts, changed the way the legal system handles crimes against children.

Amendments to the POCSO Act#

In response to growing instances of child sexual abuse and public outcry over low conviction rates, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act was amended in 2019, marking a significant move toward harsher criminal penalties. The amendment introduced the death sentence for the most serious crimes, particularly those involving minors under the age of twelve, and strengthened penalties for penetrative and aggravated penetrative sexual assault. As part of a legislative strategy focused on

deterrence, minimum terms for penetrative sexual assault were raised to 10–20 years and for serious offences to 20–life in prison.

Additionally, the amendment greatly broadened the definition of child pornography, making it illegal to produce, distribute, save, browse, or transmit child sexual abuse material (CSAM).

Pornography-related offences now carry a 3-7 year prison sentence, with repeat offences carrying a 5–10 year sentence. In addition to these modifications, the POCSO Rules, 2020 increased collaboration between police, medical authorities, and Child Welfare Committees (CWCs) and strengthened victim

protection mechanisms by requiring interim compensation and the recruitment of trained support personnel. Together, these changes sought to strengthen responsibility and improve the justice

system’s responsiveness to child victims.

Government Initiatives for Child Protection#

In order to combat child abuse, exploitation, and neglect, the Indian government has implemented a multi-layered strategy that combines institutional, legal, welfare, and awareness-based interventions in

addition to legislative change. The foundation of the law is the POCSO Act, 2012, read in conjunction with the POCSO Rules, 2020, which guarantee severe penalties, required reporting, kid-friendly practices, and temporary respite.

CWCs, Juvenile Justice Boards, Child Care Institutions, foster care, sponsorship, and rehabilitation rograms are all supported by the Integrated Child Protection Scheme (ICPS). Complementary laws that address vulnerabilities resulting from early marriage, hazardous labour, and lack of care include the Juvenile

Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, the Child Marriage Prohibition Act, 2006, and the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2016.

While the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) oversees implementation, inspects institutions, and investigates infractions, flagship programs like Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (BBBP) focus on enhancing the survival, education, and safety of girl children. The PM CARES for Children Scheme (2021), which provides financial aid, educational support, health insurance, and welfare benefits to children orphaned by COVID-19, addresses post-pandemic vulnerabilities. These programs show a move away from reactive measures and toward a framework for child protection that is more preventive and rehabilitative.

POCSO E-Courts and Fast-Track Mechanism#

The government initiated a centrally supported Fast Track Special Courts `(FTSC) program in 2019 with the goal of establishing 1,023 FTSCs, including 389 exclusive POCSO courts, to address growing pendency and delayed justice in child sexual abuse cases. There were 758 FTSCs operating in 29 States and Union Territories as of May 31, 2023, including 412 exclusive POCSO courts.

According to the POCSO Act, investigations must be completed within a month, and trials must be completed preferably within a year. By utilising the e-Courts Project, which enables e-filing, virtual

hearings, digital evidence presentation, and online case tracking, FTSCs seek to operationalise these schedules. To lessen secondary trauma, child-friendly infrastructure has been advocated, including

segregated waiting spaces, video-link testimony, one-way mirrors, and minimal direct contact with the accused. Although FTSCs have increased disposal rates in several states, their efficacy remains hindered by capacity issues and uneven implementation.

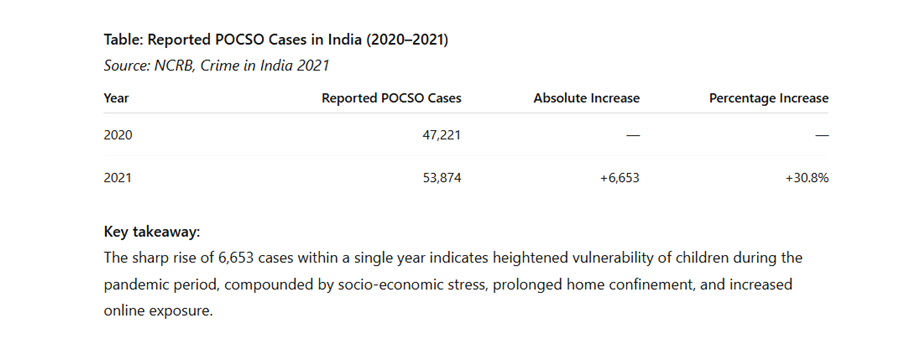

NCRB Data: A Decade of Rising Crimes Against Children#

According to NCRB data, there has been a consistent increase in crimes against children, with over 1.6 lakh cases reported each year in recent years, a sizable percentage of which are covered under the POCSO Act. This increase is attributed to both a rise in incidence and improved reporting, which is facilitated by laws mandating reporting and heightened awareness. The fact that 94–96% of offenders are known to the child—typically through relatives, neighbours, or acquaintances—is a crucial finding from

NCRB data that makes reporting and prosecution more difficult.

Concerns regarding deterrence and the administration of justice are raised by the fact that over 85% of POCSO cases are still pending in court, and conviction rates range between 30% and 35%. Although

the majority of victims are females, an increasing number of cases involving boys highlights the importance of POCSO’s gender-neutral framework.

POCSO Act Landmark Judgements#

The development of POCSO has been greatly aided by judicial interpretation. The Supreme Court rejected the “skin-to-skin” theory in Attorney General of India v. Satish Ragde (2021), ruling that sexual assault is defined by sexual intent rather than physical contact. In Independent Thought v. Union of India (2017), IPC laws were harmonised with POCSO, making marital rape of children between the ages of 15 and 18 illegal. The Act’s child-centric philosophy has been reinforced by several significant verdicts that have established age determination norms, victim identity confidentiality, and evidence standards.

POCSO Act Criticisms#

Notwithstanding its advantages, POCSOfaces numerous difficulties. The criminalisation of consensual adolescent relationships, low conviction rates brought on by shoddy investigations, uneven age

verification procedures, and trial delays in spite of fast-track procedures have all been noted by courts and academics. The death penalty clause is still controversial, with detractors cautioning that it would

discourage reporting in situations involving known criminals. Gaps in rehabilitation, compensation delays, and limited counselling infrastructure further weaken victim recovery.

Way Forward#

Expanding FTSCs, investing in investigation capacity, and providing uniform training for police, medical personnel, prosecutors, and CWCs are all necessary to strengthen POCSO. Strong rehabilitation programs, community-based reporting methods, improved child-friendly court facilities, and clear standards for

consensual adolescent cases are crucial. To ensure that POCSO fulfils its commitment to safeguarding every child’s right to safety and dignity, a change from a strictly punitive approach to a survivor-centric, prevention-oriented framework will be essential.

Clear Cut Gender Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Feb 08, 2026 6:00 IST

Written By: Nidhi Chandrikapure