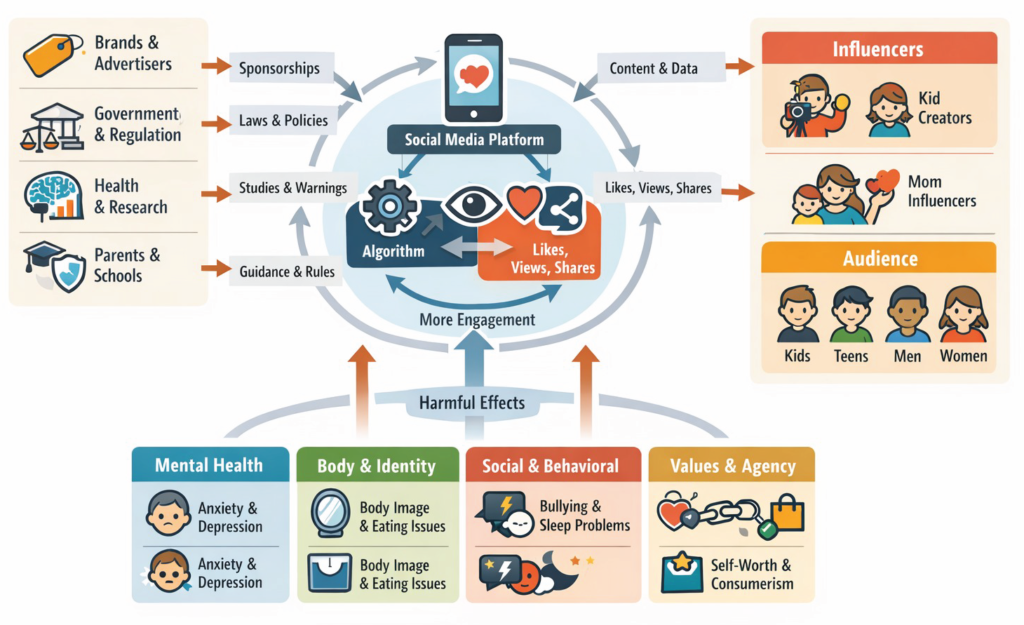

The article explores how childhood in India is being reshaped by social media, where children are both consumers and content creators, facing pressures from algorithms, parents, and brands, leading to mental, emotional, and physical challenges. It emphasizes the need for balanced guidance, mindful engagement, and protective policies to support healthy development.

In the era of reels, algorithms, subtly reshaped. What used to be a saf and subtly reshaped. What used to be a safe haven of play, seclusion, and slow self-discovery is now more often lived in public documented, loved, shared, and profited from. Children are no longer just passive social media users in India’s rapidly expanding digital economy. They are now consumers, influencers, performers, and, frequently, commodities. Long before adolescents realise the true cost of publicity, their routines become content, their faces serve as the focal point of brand advertisements, and their popularity is gauged in views. Children, parents, influencers, platforms, psychologists, and policymakers—all of whom exert influence

in ways that are frequently unequal, opaque, and profoundly consequential are among the many actors shaping this new childhood. This piece attempts to bring their interactions into sharp focus.

Today’s childhood is being quietly remade. Reel after reel, algorithm by algorithm. This article examines the various actors that shape children’s digital lives today. These include children themselves, parents acting as managers, platforms designed to capture attention and brands searching for authenticity. It also considers the concerns raised by mental health professionals about the impact on children. Ultimately, it highlights governments’ struggles to regulate a digital world. A world that is evolving faster than existing laws. The child is at the centre of it all, not only as a consumer but also as a performer, a commodity, and increasingly as a brand. This change has a distinctly gendered face in India’s thriving influencer economy. Girls make up the majority of kidfluencers, who were raised to be noticeable, pleasant, and marketable.

The argument is not about whether children should be online, but rather about under what circumstances, as India watches Australia enact a social media ban for those under 16 and its own courts start to recognise the risks associated with youngsters using the internet. This article does not portray technology as a lone villain or children as helpless victims. Rather, it depicts a complicated environment in

which accountability is frequently postponed, and authority is distributed unevenly. It poses the question of what occurs when childhood gives way to contentment, when caring turns into administration, and when maturing entails learning how to act before learning how to be.

How Did It Start? The Pandemic Effect

When COVID-19 first emerged at the end of 2019, it altered childhood, in addition to closing cities and schools. Playgrounds vanished, houses became classrooms, and screens became lifelines. The pandemic

forced children to spend more time online than ever before in a world that was already heavily digitised.

Children used laptops, tablets, and smartphones to learn, play, and keep connected when schools were closed, and physical interaction was prohibited. The amount of time spent on screens increased. Friendships, regularity, and normalcy were replaced by social media, online gaming, and video platforms. For many kids, using the internet to stay in touch with the outside world was their only option.

Digital platforms provided solace amid solitude and lessened feelings of loneliness. However, they also developed into coping mechanisms for anxiety, uncertainty, and stress. Anxiety was fueled by constant exposure to alarming news, such as an increase in cases, deaths, and economic collapse. Worldwide, about 50% of youngsters said that news about the epidemic made them feel afraid. Social media misinformation simply exacerbated the situation.

Overuse gradually replaced what had started out as necessary use. Children began using screens as a way to cope with emotional overload, terror, and boredom. Overuse of the internet undermined emotional equilibrium and decreased interest in offline life. Sleep suffering. shorter attention spans. Anxiety and depression become more prevalent.

Although it didn’t start the issue, the epidemic made it worse. It normalized continuous connectivity and reduced the age at which people were exposed to screens. While adults and teenagers have been the subject of considerable research, younger children, who are still developing their identities, habits, and feelings, were silently taking in the effects.

Even though COVID-19 is no longer present, its digital impact on childhood endures. And that’s where the actual discussion starts.

Inside the Kidfluencer Moment

In India’s rapidly expanding digital economy, children are no longer just audiences; they are creators, brands, and marketing tools. According to influencer marketing platform Qoruz, the number of Indian Instagram influencers under the age of 16 touched 83,212 by March 2025, marking a 41% rise in less than a year. Most of them are girls. Most of them are micro-influencers. And many of them are barely teenagers. Their feeds are filled with toy reviews, dance reels, fashion hauls, daily routines, and sponsored smiles. The playground has quietly moved online. Swings and slides have been replaced by likes and views. Bedtime stories are now brand collaborations.

For many of these children, the journey begins innocently with a love for performing, dancing, or storytelling. But what starts as play quickly becomes work. Algorithms reward consistency, not rest. Brand deals demand deadlines, not mood swings. Childhood, once defined by privacy and experimentation, now unfolds in the public eye. Every mistake is permanent. Every phase is archived. And every growing-up moment is watched, judged, and monetised. This shift is also reflected in aspiration. A 2024 survey found that 37% of Gen Alpha children in India want to become social media influencers. The dream of becoming an astronaut or doctor is steadily being replaced by the promise of viral fame. The question is no longer whether children can be influencers—but whether they should carry the weight of influence before they fully understand it.

Behind the Camera: Parents, ‘Momagers’, and the Rise of Mom Influencers

No kidfluencer exists alone. Behind every viral child is an adult managing the account, approving content,

negotiating brand deals, and deciding what aspects of childhood to share publicly. Enter the momfluencer—a growing force in India’s influencer economy.

According to influencer marketing platform Qoruz, the number of Indian Instagram influencers

under the age of 16 touched 83,212 by March 2025, marking a 41% rise in less than a year. Most of

them are girls. Most of them are micro-influencers. A 2024 survey found that 37% of Gen Alpha children in India want to become social media influencers. The dream of becoming an astronaut or doctor is steadily being replaced by the promise of viral fame.

India had over 3.79 lakh parenting influencers on Instagram by March 2025, according to Qoruz. Nearly 64% of them are women. Many began by sharing pregnancy journeys, parenting tips, or daily family life. Over time, children naturally became part of the frame first casually, then consistently. For some families, social media became a source of income. For others, a full-time profession.

This is where the line between parenting and production begins to blur. Children appear in reels because brands prefer “real families”. A tantrum becomes content. A birthday becomes a campaign. A school

morning becomes a vlog. While many parents insist their children enjoy the process, the power imbalance is impossible to ignore. Can a child truly give informed consent when the camera is always on? Can

they opt out when the family’s livelihood depends on engagement?

Some parents are cautious. They limit screen time, avoid comment sections, and seek their child’s permission before posting. Others treat content creation as a structured routine, similar to extracurricular

activities. But unlike dance classes or sports practice, social media offers no clear boundaries. There are no fixed hours. No labour protections. No guaranteed privacy. Momfluencers, too, are now feeling the pressure of changing platform rules. As age restrictions tighten, many see this as an opportunity to shift the focus back to adult-led content. Yet the ecosystem they helped build still relies heavily on children’s visibility. The child remains the hook—even when the adult holds the handle.

India Rethinks Children’s Social Media Use, Australia Shows the Way

As governments grapple with the growing risks of children growing up online, Australia’s under-16 social media ban is emerging as a global reference point—one that India’s courts and policymakers are now

beginning to look toward in shaping their own child digital safety framework.

Australia’s decision to prohibit minors under the age of sixteen from using social media is a significant change from recommendations to binding laws. The rule, which is framed as a child-safety precaution,

assigns platforms full accountability by requiring age verification, removing accounts belonging to minors, and imposing severe fines for noncompliance. Australiahas established itself as a global test case

for whether the state can effectively participate in children’s digital lives, despite ongoing enforcement issues and privacy concerns.

This regulatory urgency is now being echoed in India, albeit in a different way. Recent observations by the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court indicate a judicial acknowledgement of the same problems

mentioned by Australia: children’s increased vulnerability online, easy access to bad content, and cyber exploitation. The court situates India’s concerns within a global policy discourse by specifically mentioning Australia’s ban on players under the age of 16. It also calls for immediate action through awareness, parental controls, and child-rights education, and urges the Union government to consider similar legislation.

The Indian strategy is incremental rather than prohibitive, at least for the time being. The focus is on platform compliance under current IT regulations, parental accountability, and user regulation rather than a complete ban. However, the underlying message is evident: dispersed awareness efforts and voluntary measures are no longer considered adequate. Similar to Australia, the emphasis is shifting toward formal legislation, more transparent intermediary responsibility, and a more robust state role in regulating children’s digital environments.

Australia is not the only country in the world. While countries like Malaysia and New Zealand are considering more stringent regulations, others, such as Denmark, France, Germany, the UK, and

numerous US states, are revisiting age thresholds, parental permission models, and platform obligations. Together, these actions demonstrate a growing understanding that strong legislation, enforced compliance, and cross-border coordination are now essential to protect children online, in addition to parental vigilance.

The Anxious Generation: When Childhood Moved Online

In his book, “The Anxious Generation”, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt makes a claim that feels both unsettling and painfully familiar: something fundamental broke in childhood around the early 2010s. Rates of anxiety, depression, self-harm, and loneliness among children and adolescents began rising sharply—not gradually, but suddenly. This was not a slow cultural drift. It was a rupture.

Haidt contends that the timing is not coincidental. Childhood crossed an invisible line around 2012. The game was moved inside. Independence decreased. Additionally, social media and smartphones have become constant companions, particularly for teens and preteens. Children’s social lives were rearranged

around technology, not only adopting it.

This change from a “play-based childhood” to a “phone-based childhood” is what Haidt refers to. Children in previous generations developed resilience through activities such as climbing trees, engaging in face-to-face arguments, experiencing boredom, and solving problems independently. There was

minimal physical risk, and recuperation was quick. A fall caused pain before healing. The battle came to a conclusion, and then moved on. Errors and forgetfulness were common in childhood.

India had over 3.79 lakh parenting influencers on Instagram by March 2025, according to Qoruz. Nearly 64% of them are women. Many began by sharing pregnancy journeys, parenting tips, or daily family life.

Over time, children naturally became part of the frame—first casually, then consistently. For some families, social media became a source of income. For others, a full-time profession.

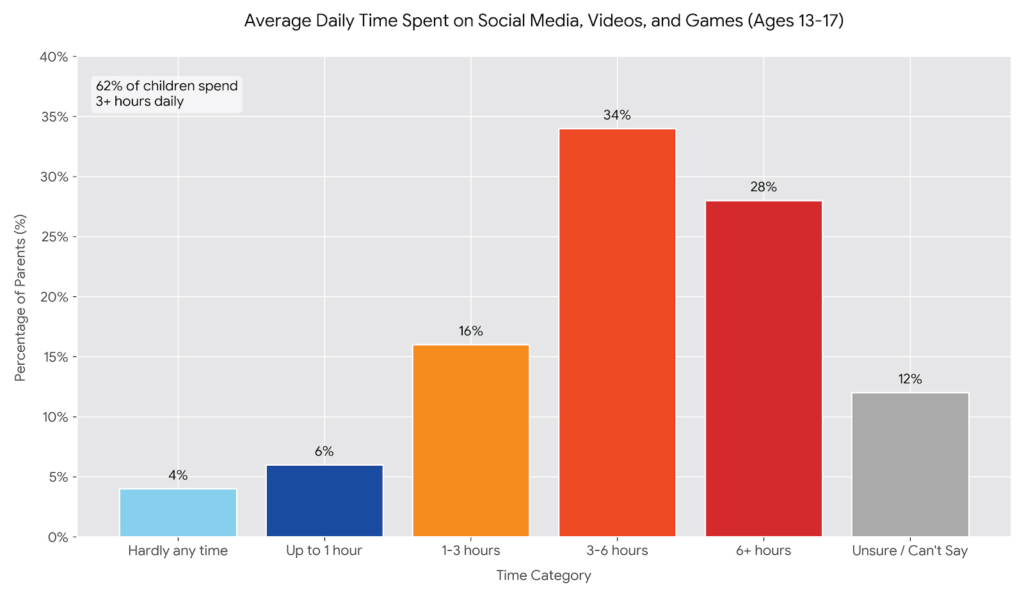

Crisis in the making: Over 40% urban Indian parents admit their children between ages 9–17 are addicted to videos, gaming & social media

- 55% urban parents say their children aged 9–13 years have access to smartphones for all or most of their day (outside of in-person school classes)

- 71% say their children aged 13–17 have access to a smartphone for all or most of day

- Parents believe their habit of using gadgets excessively and giving early access to children along with school activity becoming online during pandemic are key reasons for addiction

- 68% parents believe the minimum age to open a social media account must be raised from 13 to 15

Source: Based on findings shared by LocalCircles, a community social media platform that enables citizens and small businesses to escalate issues for policy and enforcement interventions.

This is not how the digital world operates. Errors on the internet persist. Embarrassment is stored away. Likes, views, and following counts are used to measure rejection. Social comparison is a constant. This continuous exposure is too much for a developing brain that is still learning to control its emotions.

The impact of social media on identity development is one of Haidt’s most important cautions. Adolescence is a time for introspection: Who am I? Where am I supposed to be? These questions are relentlessly—and frequently cruelly answered by social media. Rather than meaning, it provides metrics.

Approval turns into a number. Silence feels like rejection. Popularity becomes visible, permanent, and brutally public.

Haidt observes that girls seem especially susceptible. Image-based platforms increase self-surveillance, appearance based validation, and body comparison. Anxiety frequently manifests as withdrawal, perfectionism, or silent self-loathing rather than as panic. Boys, on the other hand, withdraw into

virtual worlds and video games, frequently at the expense of social skills and emotional expression in the real world. The isolation remains the same, but the results differ.

The Anxious Generation’s most unsettling revelation is that good parenting is no longer sufficient on its own. Platforms that are designed to circumvent boundaries, exploit psychological vulnerabilities, and foster compulsive involvement pose challenges for even watchful and well-intentioned parents.

Youngsters quickly acquire the skills necessary to conceal apps, create multiple accounts, and maintain parallel online lives. Supervision becomes a catch-up game.

He advocates for group accountability—what he refers to as a “rewiring” of children. Delaying smartphone use, reinstating unsupervised play, rebuilding platforms with child safety at their centre, and viewing mental health as a public issue rather than a personal failure are some examples of how to do this.

The Anxious Generation is fundamentally not opposed to technology. It is in favour of children. It poses a dilemma that reverberates throughout households, classrooms, and playgrounds.

The Hidden Costs of Childhood on Social Media

These days, viewing endless short videos, swapping pictures, and scrolling through reels are no longer just pastimes for grown-ups. They are a part of everyday life for today’s kids. Posting well-chosen photos of joy has become the “new normal,” influencing not only how children engage with friends but also how they view the world and themselves. Experts caution that social media has a hidden cost to young, growing minds despite its promises of connection, creativity, and enjoyment.

Early adolescence and childhood are critical periods for brain development. Attention and self-regulation are developing, emotional abilities are changing, and neural pathways are growing. According to Dr Vinit Banga, Director of Neurology at Fortis Hospital in Faridabad, “At this point, external influences have a much deeper impact, and social media has emerged as one of the most powerful influences in a child’s environment.”

The impact of social media on attention spans is one of its most obvious impacts. Platforms are designed to be quick, providing immediate satisfaction for likes, comments, and shares. Dr Banga cautions that children’s brains become accustomed to constant novelty, which makes it more difficult for them to concentrate on activities that call for patience, such as reading, learning, or engaging in creative play. Teachers and parents are the first to notice that children who spend a lot of time online find it difficult to focus, quickly lose interest, and grow irritated when tasks take a long time.

Another casualty is emotional well-being. Self-esteem is gradually eroded by endless feeds of idealised bodies, lifestyles, and accomplishments. Another casualty is emotional well-being. Self-esteem is gradually eroded by endless feeds of idealised bodies, lifestyles, and accomplishments. Stress is increased by unfavourable remarks and the need to appear “perfect” online, which frequently manifests as irritation, withdrawal, or anxiety. “Children’s self-worth starts getting tied to likes and comments rather than real-life relationships, leaving them emotionally vulnerable,” says Dr Supriya Mallik, Consultant Developmental Psychologist at Embrace X Madhukar Rainbow Children’s to Hospital in Delhi.

Physical well-being also declines. Melatonin production is suppressed by late-night screen usage and scrolling, which can interfere with sleep. Insuffi-cient sleep contributes to feelings of fatigue, irritability, impaired concentra-tion, and poorer academic performance. The cycle is repeated: social media frequently upsets the delicate balance between mental, cognitive, and physical health.

Safety and privacy are additional issues. Due to their lack of control over their digital footprints, children are susceptible to data exploitation, hazardous informa-tion, and cyberbullying. Social confidence and emotional stability may be impacted by the invisible burden of being “always online.”

Is social media prohibition the solution, then? No, experts say. A methodical, supervised approach is more effective. Children can safely navigate online spaces by delaying exposure, establishing clear screen-time limits, fostering offline interests, and teaching digital literacy. While in-person connections foster resilience, creativity, and emotional development, limiting social media use can help reduce anxiety, improve sleep, and enhance focus.

According to Dr Vinit Banga, Director of Neurology at Fortis Hospital in Faridabad, “At this point, external influences have a much deeper impact, and social media has emerged as one of themost powerful influences in a child’s environment.”

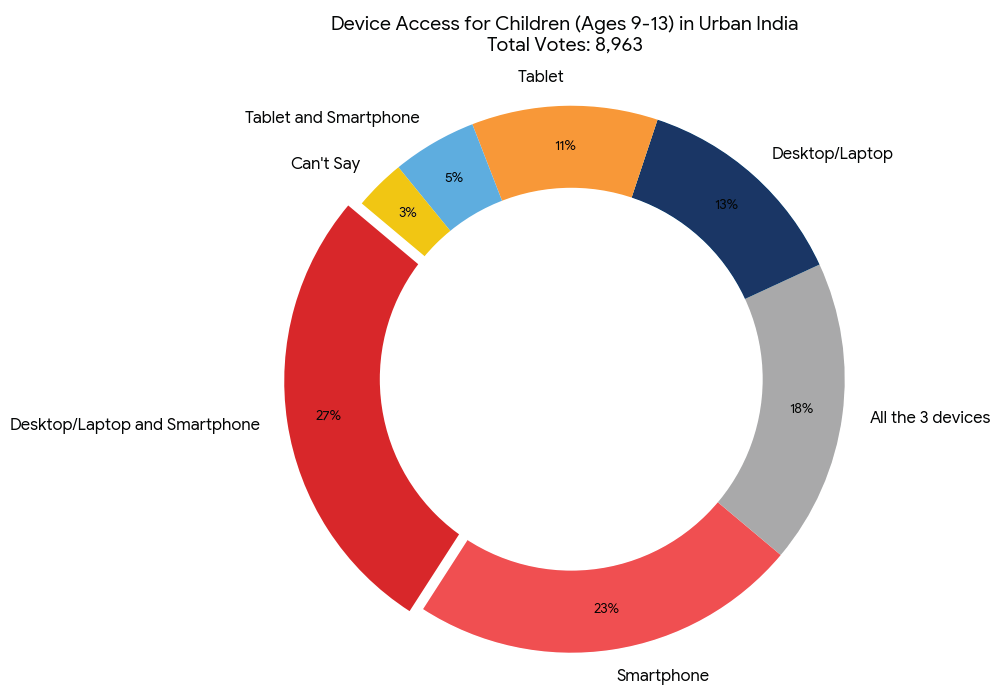

The graphs show that children in metropolitan India between the ages of 9 and 13 are becoming more

dependent on technology. It brings out data released by LocalCircles, a community social media platform

to escalate issues for policy and enforcement responses. According to data on device access, smartphone either alone or in conjunction with laptops and tablets—dominate children’s internet access to several devices, which emphasizes how simple it is to stay connected unsupervised outside of school hours.

This trend is further supported by the donut chart, which shows the share of users in Urban areas, has

access to both computers and cellphones. All of these trends point to how deeply ingrained digital devices are in kids’ daily life, which raises issues with screen addiction, decreased physical activity, and the need for more robust parental supervision and legislative measures to encourage safe and balanced digital use.

Source : Based on findings shared by LocalCircles, a community social media platform that enables

citizens and small businesses to escalate issues for policy and enforcement interventions

2026Breaking the Cycle of Anxiety

Children can re-establish a connection with intrinsic motivation and real-world accomplishments when social media is reduced or eliminated as a source of validation.

Encouraging Healthier Alternatives

Experts emphasise that cutting back on screen time works best when combined with meaningful offline interaction. Experts suggest engaging in activities that promote mental, emotional, and physical health in place of passive scrolling. Hiking and team sports are examples of outdoor activities that reduce stress while fostering social skills and resilience. Art, music, and crafting are examples of creative endeavours that promote concentration and emotional expression. While offline games like chess and puzzles improve patience and critical thinking, communi-ty involvement, especially volunteering,

promotes empathy and teamwork. While practical STEM projects foster curiosity and problem-solving, physical activities like yoga and dancing promote mood stability and improved sleep. Journaling and meditation are two other mindfulness exercises that support children’s growth in self-awareness and emotional control.

The Benefits of Reduced Screen Time

Reduced screen time offers significant benefits for both physical and mental health. Reducing screen time enhances sleep quality by lowering exposure to blue light, which is known to disrupt the production of melatonin. Consequent-ly, improved sleep promotes memory, focus, and emotional equilibrium. Stronger engagement with the world outside of screens and better academic performance are the results of structured screen-time limits, which also promote healthier daily routines.

Conclusion:The Complex Interplay of Digital Actors

The children themselves—the performers, the watchers, and the creators—are at the centre of this digital world. Their bodies, thoughts, and emotions are developing, brittle, and susceptible to influence. Everything else revolves around them. Children’s perceptions, desires, and imitations are shaped by influencers and content producers.

Algorithms normalise comparison, promote trends, and reward participation. Likes and shares quantify approval, making one’s value evident. The speed and complexity of online environments frequently outstrip parents’ and caregivers’ efforts to safeguard, control, and guide. While some try to protect their kids from the worst of the digital tide, others take on the role of managers, striking a balance between opportunity and supervision. By researching attention spans, emotional resilience, sleep habits, and mental health, psychologists and educators raise concerns.

Protective ecosystem, however, remains uneven and reactive. Regulatory measures often lag behind the pace at which platforms evolve. Australia and other nations have explicit age limitations. Platform compliance, parental accountability, and gradual frameworks are being tested in India. Laws can establish limits, but they cannot replace direction, compassion, and practical experience. Together, platforms, legislators, parents, and mental health professionals create a complex ecosystem that aims to protect

children while fostering growth, connection, and creativity.

Everywhere you look, the effects of unbalance are evident. Attention can be broken by excessive exposure. Self-esteem can be damaged by idealised pictures. Scrolling late at night can interfere with sleep. Emotional and social security may be jeopardised by vulnerability to cyberbullying and data misuse.Identity formation, social skills, mental health, and physical health are all closely related. The system is affected by a single weak link. Risk is multiplied by a single failure to protect or educate.

Conversely, thoughtful boundaries, mindful engagement, and informed guidance can strengthen resilience.

At the centre of this digital world are children, whose development is both remarkable and delicate. Every choice kids make directly affects them. The content they watch, the influencers they follow, the guidelines set by their parents, and the laws passed by their government. They are fundamentally creative, inquisitive, and self-assured. This core is surrounded by platforms, parents, psychologists, and lawmakers, all of whom shape, nudge, or restrain in both visible and unseen ways. Social media is neither good nor bad. Its ability to engage developing minds is what gives it its power.

Finding a balance between opportunity and protection, visibility and privacy, involvement and well-being is an obvious difficulty. Children’s mental and physical well-being must not be sacrificed in the name of exploration, expression, and connection. Safety should take precedence over attention on platforms. Parents need to provide guidance, but not total control. Policies must safeguard without dehumanising.

Research must be translated into useful action by psychologists and educators. Society can only guarantee that children become not only digitally literate but also robust, self-assured, and emotionally healthy by acknowledging this complex, interconnected environment.

Clear Cut Research Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Feb 16, 2026 9:00 IST

Written By: Nidhi Chandrikapure