India’s economy has been booming: real GDP growth recently rose by 7.8% in Q1 FY 2025-26, and official figures show India’s output surpassing Japan to become the world’s fourth-largest economy (PIB, 2025). And is on track to become the world’s third-largest economy India is project-ed to be the world’s fastest-growing major economy (6.3% to 6.8% in FY 2025-26). Driven by robust domestic demand, a dynamic demographic profile, and sustained economic reforms, India is asserting its rising influence in global trade, investment, and innovation.Currently the world’s fourth-largest economy, India is on track to become the third-largest by 2030 with a project-ed $7.3 trillion GDP. This momentum is powered by decisive governance, visionary reforms, and active global engagement. Notably, growth is accel-erating, with real GDP expected to rise by 7.8% in Q1 FY 2025-26, up from 6.5% a year earlier (Source: PIB).

Yet this success is tempered by linger-ing hardship. Despite a soaring stock market and robust growth, the govern-ment still distributes subsidized food to roughly 800 million people, well over half the population. PLFS (June 2025) shows the unemployment rate rises to 5.6%, and female joblessness is higher at 5.8%. Oxfam (2023) reveals that the wealthiest 1% of Indians possess about 40% of the nation’s total wealth, and the bottom 50% hold merely 3%.

Currently the world’s fourth-largest economy, India is on track to become the third-largest by 2030 with a projected $7.3 trillion GDP.

In other words, India’s challenge is to translate headline GDP figures into broad-based well-being. The coming years will test whether the country’s economic policy can “balance” high growth with inclusive growth and India’s GDP and Well-Being

The year 2024 had seen major events like over fifty percent of the global population participating in major elections worldwide, detrimental events such as the Russia-Ukraine crisis and the Israel-Hamas conflict. These condi-tions affected energy and food security, resulting in increased prices and escalating inflation. Additionally, these occurrences redefined international commerce. Geopolitical uncertainties and policy ambiguity, particularly concerning trade policies, have exacer-bated volatility in global financial markets. Despite these conditions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that the global economy will increase by 3.2% in 2024 and 3.3% in 2025. For India, the real GDP growth rate is projected at 7% for 2024 and 6.5% for 2025 (World Economic Outlook), which is double the globalrate. The Great IndianBalancing ActCOVER STORY / The Great Indian Balancing Act.

India’s size and pace of growth are impressive. The National Statistical Office reports GDP rising 8.2% in

FY2023–24, up from 7.0% the year before. In 2025, it became the fourth-largest economy with a GDP of

$4.18 trillion in merely 11 years from $2 trillion in 2014, according to NITI Aayog’s CEO BV ubrahmanyam. The IMF forecasts that by 2028, India will overtake Germany to become the 3rd largest economy worldwide. Still, that wealth is spread thinly across 1.4 billion people. Only in recent data has extreme poverty fallen to single digits. For example, a World Bank poverty line of $3.00 a day (2021 prices) leaves only about 5.3% of Indians below it, a remarkable improvement from a decade ago. In short, while spectacular growth has dramatically shrunk India’s poverty headcount, the country is still home to tens of millions just above the poverty line. Most of India’s growth is driven by its domestic market. Close to 70% of GDP comes from household consumption, making India the world’s third-largest consumer market. This massive internal demand has shielded the economy even as exports and investment falter. But

high consumption also means India must wring efficiencies from within, and rising incomes are uneven. Health and education spending remain well below OECD norms, and many essentials like clean water, sanitation, and schooling have not kept pace with income growth. In practice, India is learning that GDP figures alone can be misleading: a trillions dollar economy can still see large swathes of the population

struggle with basic needs.

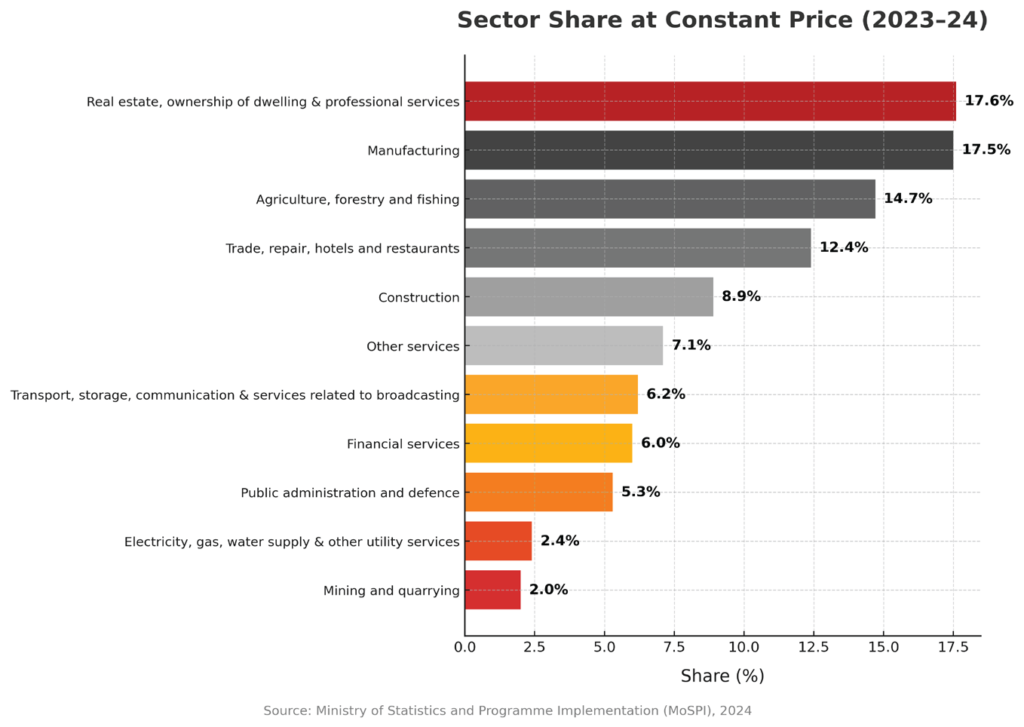

The character of India’s growth is changing too. Agriculture now accounts for only about 15% of GDP, even though roughly half the workforce lives off the land. By contrast, services now generate more than half of GDP, led by IT, finance, and retail. Industry (manufacturing, construction, etc.) contributes the rest. The shift is visible in recent numbers. In FY2023–24, farm output grew only about 1.4%, barely keeping

pace with population. Mining was unusually strong at 7.4% growth, but its share of GDP is small. The real dynamism was in industry: the secondary sector expanded 9.7%, led by nearly 10% growth in manufacturing and construction. In short, India is moving from a rural economy toward cities and

factories, but the transition has been slower than in some East Asian countries. This matters because high growth in manufacturing and skilled services is traditionally shown to increase incomes across society, rising together, a lesson Indian economists often note. Yet the structural transition has not solved all problems. Millions of Indians are stuck in low-productivity jobs. For example, manufacturing’s share of GDP has hovered near 15% for decades, limiting job creation. Many workers remain in low-paid informal work or unpaid family farming. One consequence is that productivity per worker in India is still among the lowest in the world. Indians work long hours, but output per hour lags China and other emerging markets. Upgrading skills and expanding factories will be critical if India’s next phase of growth is to lift

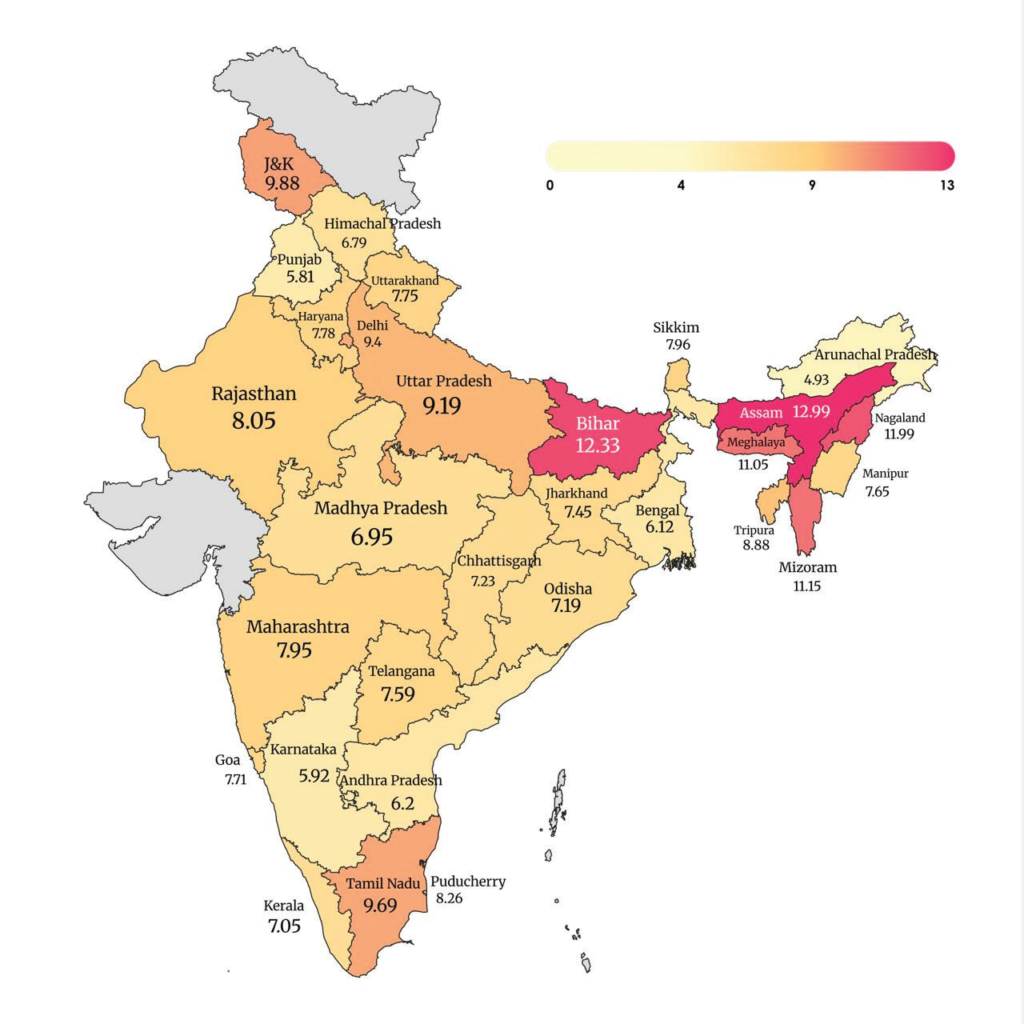

living standards. The State-Level Story India’s growth is also highly uneven across regions. A handful of prosperous states account for the lion’s share of output. NITI Aayog has highlighted that high-income states (home to just 26% of India’s people) generate 44% of GDP, whereas low-income states (38%

of the population) contribute only 19%. COVER STORY / The Great Indian Balancing Act 35 / clearcutmedia.co.in

Put another way, states like Maharash-tra, Tamil Nadu, and Gujarat, with fewer people, have vibrant industries and services, while larger states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, or Madhya Pradesh lag. This north-south and urban-rural divide reflects differences in education, infrastructure, and invest-ment. The Vice-Chairman of NITI Aayog highlighted that “the develop-ment strategy that’s appropriate for Tamil Nadu or Bihar will necessarily be very different”. In practice, this means policy must be tailored: lagging states need more capital and skills training, while richer states need to focus on innovation. Bridging this gap is a core challenge: without it, India’s overall averages (like national GDP growth) will hide a deep pocket of under-devel-opment.In 2023–24, Uttar Pradesh emerges as the leading contributor, highlighted in the darkest shade, with a share close to 9.7%, indicating its strong economic base. States like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and Karnataka also show relatively high contributions, reflecting their industrial and service sector strength. In contrast, northeastern states and smaller regions exhibit minimal shares, around 0.27%, due to lower industrialization and economic activity. Overall, the distribution reveals regional disparities, where a few large states dominate national output, emphasizing the need for balanced regional development (Figure 2).The disparities show up in social indicators, too. Southern states tend to have higher literacy and life expectan-cy, whereas poorer states have larger “demographic dividends” (more youth relative to retirees) but also higher unemployment and poverty. In recent years, some traditionally backward states (often dubbed BIMARU: Bihar,

Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh) have improved school enrol-ment and health indicators faster than richer states. This suggests a silver lining: poorer regions can grow faster if they invest in people and governance. The trick is keeping that momentum going.

Tax Reforms and Fiscal Challenges#

A crucial but less visible part of the balancing act is finance and taxation. Despite high growth, India’s tax revenues remain low by global standards. Central government tax collection is only about 11.7% of GDP (with direct taxes around 6.6% of GDP and indirect taxes 6.86% FY 2023-24). By comparison, advanced economies often collect twice that share.

Moreover, only about 5% of Indians actually file income tax returns, a reminder that most of the economy remains informal or uses exemptions. The low tax take constrains spending on roads, schools, and healthcare, forcing states and the Centre to run large budget deficits.

One landmark reform has been the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Launched in 2017, GST subsumed many state and federal indirect taxes into a single system. India now often revenues per month. But it also required careful balancing. Recently Centre implemented GST 2.0. Reforms in September 2025.

The reforms will boost private consumption, which is expected to increase GDP growth by 20-60 bps. A

reduction in GST taxes has a higher multiplier effect (1.08x) than direct taxes because it is an indirect tax that applies to the entire population at the point of sale. This will also help in reducing the headline inflation. Although the extent of headline rate reduction may vary depending upon the extent of pass-through of rate cuts by corporates to the consumers. If the pass-through is full, then inflation may

be reduced by 60 to 100 bps. Apart from a GDP boost, the rate cut will help in reducing the price of key essential drugs and medicines, reducing the out-of-pocket expenses of households. A drastic reduction of GST on the purchase of small cars and commercial vehicles from 28% to 18% will give a permanent demand boost and will give immediate respite to households. The rate cut will negatively impact the tax

collections of central and state governments, and the annual revenue loss

could be of Rs. 0.7 to Rs.1.8 trillion, with states shouldering a higher burden of loss. This may result in a reduction in Public Expenditure (Welfare and Subsidies), an increase in Fiscal Deficit and borrowings, and and negatively impact economic growth However, this may be partially offset by up to 40% tax imposed on ultra-luxury and sin products. The rate cut will also partially offset the negative impact of the higher

import tariffs of 50% imposed by the US. Here, economic policies need a balanced strategy to minimize losses and increase public expenditure. As it stands, the government faces a balancing act between keeping taxes low enough to encourage business and high enough to fund development.

Unemployment and Inequality#

Even as GDP numbers shine, millions of Indians remain under-employed and poor. Independent think tank Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) surveys estimate the unemployment

rate at roughly 7% in mid-2024 – much higher than the official government figure and far above the 6% seen before the Covid slump. In fact, a recent poll of economists it was observed that the lack of jobs will be the biggest economic challenge for India in the coming years. Many observers say that India’s growth

has been insufficiently “inclusive”; too few manufacturing or public works jobs have been created. For example, the flagship rural employment program (MGNREGA) still provides about 100 days of paid work annually to wages barely above $4 per day. At the same time, income and wealth in India are highly concentrated.

“The top 1 percent in India now owns more than 40.5 percent of total wealth in 2021, while the bottom 50% of the population (700 million) has around 3 percent of total wealth”. -Survival of the Richest: The Indian Supplement (Oxfam India) “

Clear Cut Startups Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Jan 20, 2026 09:00 IST

Written By: Rajani Singh