As India gets ready for the Union Budget 2026–2027, consultations between ministries and agencies have started. Bringing the Gender Budget, an important component of the country’s budgeting process back into the spotlight. The Gender Budget Statement (GBS) is a standard component of fiscal planning now. It is more important than ever in promoting gender-responsive governance. Last year’s GBS 2025–26 revolutionary potential was constrained by significant fundamental flaws in methodology, data infrastructure and outcome monitoring. We need to ensure that gender allocations accurately reflect women’s needs on the ground. It is also crucial to review these deficiencies when the forthcoming budget negotiations take place. Improving the quality, targeting and evidence base of gender-related expenditures must take precedence over incremental increases in allocations.

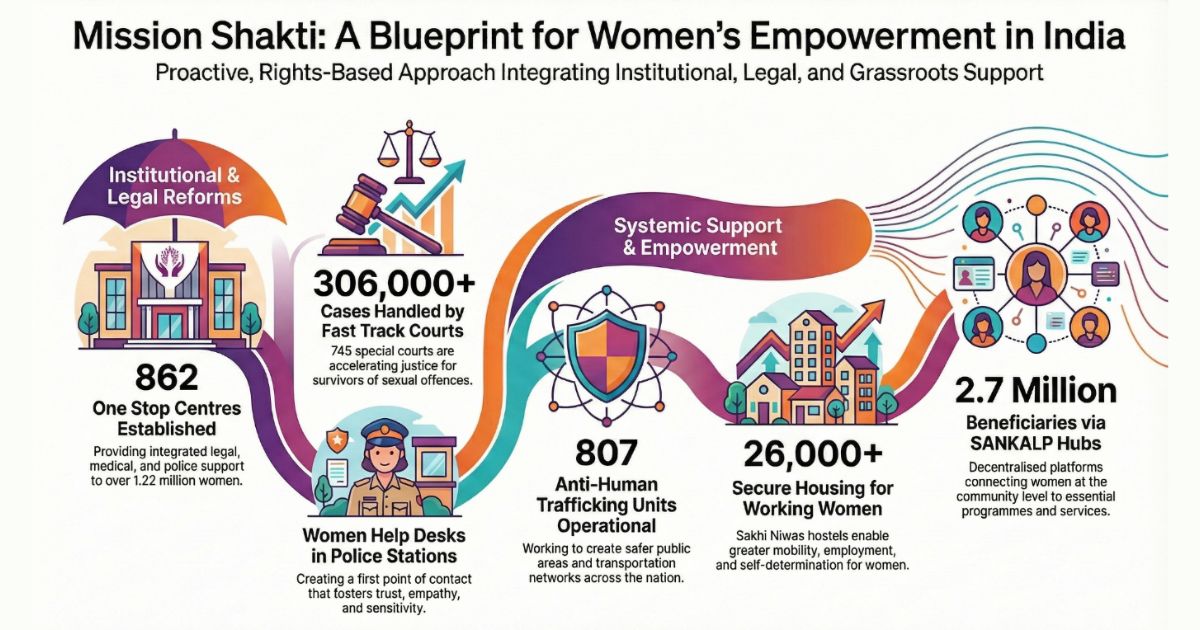

The Gender Budget Statement (GBS) 2025-26 contributed to gender-responsive budgeting (GRB), with increased allocations and wider participation from ministries. The gender budgeting experiments have been carried out within the overall macro-fiscal rule’s framework of India. It was instructed to undertake fiscal consolidation by maintaining the fiscal deficit-to-GDP ratio at 3% and with a “golden rule” of phasing out the revenue deficit (Lekha Chakroborthy, 2025). It was India’s largest-ever gender budget, boosting women’s welfare, education, and economic empowerment. It had 49 ministries reporting gender-specific allocations yet its transformative potential was constrained by execution and structural issues. These generally stem from the unclear methodology for assigning funds. Also, there are inadequate tracking methods, poorly done gender impact evaluations and a dearth of gender-disaggregated data, monitoring and evaluation procedures. These inadequacies make it challenging to determine the true results of gender-focused initiatives or to appropriately assess women’s needs. Some of the discrepancies as pointed out by the scholars. For instance, expenditure on Research Studies by ICMR under the Department of Health Research is featured in part A of the FY22 Gender Budget. There is no clarity as to how it has 100% women beneficiaries or how it contributes to women empowerment and correcting gender imbalances. Additionally, the goal of the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana–Grameen (PMAY-G) is to encourage women to own homes. There is a disconnect between the program’s objectives and results. Only over 23% of homes are really owned by women, despite being designated under Part A of the Gender Budget as entirely benefiting them. Furthermore, there is little room for other sectors because about 90% of gender budget allocations are focused on a few significant welfare programs including PMGKAY, MGNREGS and PMAY-G. Long-term initiatives like Ayushman Bharat and Awas Yojana also take funds away from initiatives like women’s education, skill development and Mission Shakti that can provide quicker and more immediate advantages for empowerment.

Recommendations and Way Forward:

1) The gender-responsive budgeting (GRB) method should be incorporated at the project design stage. In order to effectively assess requirements and create evidence-based initiatives like crèches or dormitories, ministries must first collect gender-disaggregated infrastructure and workforce data.

2) Nations that incorporate GRB findings into budgetary allocations, demonstrate greater progress in reducing gender disparities in political involvement and development. Thus, gender equality outcomes represented in indices like the GDI, GGI, and GII can be improved by aligning GRB with national goals and SDG targets.

3) Data gathered at local levels should be incorporated into national budgets. It should also be considered by ministries in allocating funds for national schemes. The collection and disaggregated presentation of data at the local level will only help in improving the efficacy of the schemes. Collecting disaggregated data for better information on the distribution of resources among male and female beneficiaries at local levels would provide better and more evidence-based grounds for decision-making and will contribute to ensuring that public funds are used more effectively.

4) Economist Nirmala Banerjee proposes dividing public spending on women into three categories: First, empowerment programs that actively lessen gender-based disadvantages and advance equality, second, gender-reinforcing assistance that supports women’s traditional roles and third relief measures that offer short-term assistance without addressing structural issues.

5) Debbie Budlender’s five-step framework for GRB can be taken into consideration to create a more efficient and goal-oriented gender budget:

(a) Examining the treatment of women, men, girls and boys.

(b) Evaluating gender-responsive policies.

(c) Determining the sufficiency of budgetary allotments.

(d) Tracking expenditures and service provision and evaluating results.

The 2026–27 Budget can build on the lessons learned from the previous year. Additionally, coordinating gender budgeting with SDG commitments and national development goals will guarantee that funds result in quantifiable advancements. These are rooted in women’s participation, health, education and economic empowerment. The forthcoming budget offers a crucial chance to transition from symbolic allocations to real, equity-driven budgeting. It contributes to promoting gender justice in a consistent and quantifiable manner as India progresses toward a more inclusive fiscal policy architecture.

Clear Cut Gender Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Dec 05, 2025 12:54 IST

Written By: Nidhi Chandrikapure