A family migrating | Photo Credit: Internet

Clear Cut Research Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Oct 14, 2025 06:06 IST

Written By: Janmojaya Barik

In Bihar, the term palayan is a part of everyday parlance. It refers to migration, but for most families, it has a connotation far greater than that. It reflects separation, difficult decisions, and the hope that the next day will be somewhat better than the last.

Understanding Palayan

Palayan occurs when individuals exit their villages in search of work or residence elsewhere. In Bihar, it is predominantly labour migration. Individuals migrate to other states or abroad due to the lack of employment at home. Bihar and Uttar Pradesh together account for over a third of India’s internal migrants, as reported by the World Bank’s India Migration Report 2024. Over 74 lakh individuals from Bihar reside and work outside the state.

Young men aged 18 to 40 are the majority among migrants. They work in construction camps, factories, hotels, and delivery businesses in cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Surat, and Ludhiana. Some of them go away for a few months and come back home during the festival or harvest seasons. Others remain away for years.

Why People Leave

Bihar’s economy remains agrarian-based. Almost 70 percent of its population relies on agriculture, but the state’s income comes only from less than 20 percent of agriculture. Landholdings are limited, rainfall is unpredictable, and floods ruin crops in most northern districts nearly every year.

As of 2023–24, Bihar’s youth unemployment rate stands at 9.9%, with urban areas at 22.2% and rural areas at 8.8%. This indicates a significant improvement from previous years but still highlights a concerning trend. Notably, unemployment is highest among graduates (14.7%) and postgraduates (19%), underscoring the challenges faced by educated youth in securing employment according to The Quint

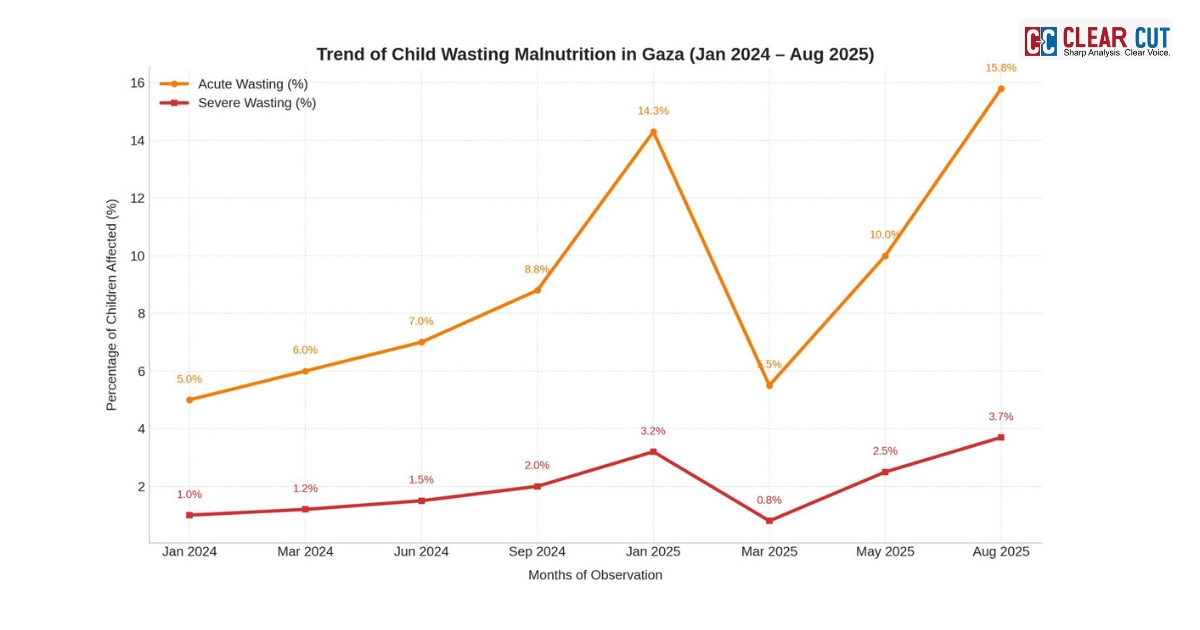

Where do Migrants go ? | Photo Credit: EPRA Journals

The Money That Keeps Bihar Running

Remittances take money home. The World Bank estimated in 2023 that in one year, Bihar got around 85,000 crore rupees as remittances. That is almost ten percent of the state’s economy.

Families spend this money on food, school fees, and small house construction. The Institute for Human Development’s research demonstrates that families receiving money from migrants spend between 30 and 40 percent more on education and health than those who do not. Migration, thereby, sustains rural Bihar in the form of an informal welfare system.

The Hidden Cost of Migration

The economic benefit may conceal emotional cost. When men emigrate, families are split. In a 2022 study by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, an estimated 60 percent of children living in migrant households have one missing parent. Women do farm work, finances, and household chores, sometimes without cover or protection.

The children in such households are likely to leave school earlier, particularly girls who assume domestic work. City migrants suffer as well. Almost 80 percent of Bihari laborers are working in the unorganized sector without any contract, job security, or social safety net. They have small rooms and lack ration cards or government health services since these are linked to their native districts.

The 2020 COVID-19 lockdown showed the vulnerability of this system. Over 20 lakh workers came back to Bihar at that time, with many having to walk long distances. Although there was temporary assistance by the state, most of them had to come back to cities eventually, since working from home still wasn’t that great.

What Is Changing

In the recent past, Bihar has attempted to bring down its reliance on migration. The Bihar Skill Development Mission and the Kushal Yuva Program have given training in computers and communication skills to over 30 lakh young people. The Mukhyamantri Udyami Yojana provides small entrepreneurs with loans and grants.

There are also fresh initiatives to bring industry into textiles, food processing, and green energy. Yet, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy in 2024 said Bihar’s labour participation rate remains around 36 percent, which is amongst the lowest in the country. This indicates that generating jobs locally is not yet adequate to absorb young workers.

Looking Ahead

Migration is not always bad. It has enabled millions of people in Bihar to escape poverty and educate their children. It has integrated rural Bihar into the rest of India and made families financially secure.

But migration is a problem when it is forced. When individuals move away because there are no opportunities in their homeland, it indicates an economic failure. Bihar must generate employment locally. It must also have better social protection for migrants wherever they are working so that they are treated with dignity and fairness.

According to economist Jean Drèze, migration is not the disease, but the symptom. Bihar’s task is to treat the causes of its unemployment, poverty, and poor rural development.

When that happens, the term palayan might no longer connote fleeing. It might just signify movement, prompted by ambition, rather than desperation.