Photo Credit: NYT

Clear Cut Research Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Oct 12, 2025 11:30 IST

Written By: Janmojaya Barik

When the initial tanks crossed into Ukraine in February 2022, the initial images were of ruined cities and people on the move. But behind the battle lines, a different, unseen fight started — one waged not with guns, but with wheat, gasoline, and fertilizer.

A new analysis released by Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems and authored by Dr. Dilshad Sarwar and Sara Rye (2025) follows this covert war across seas and borders. The article surveys 22 studies published from 2022 to 2025 in an effort to grasp how the conflict has rattled world supply chains — particularly food and energy systems — and what that does to millions of people’s daily meals.

The War That Emptied Baskets

Prior to the war, Russia and Ukraine collectively represented close to 30% of world wheat exports and 80% of sunflower oil exports. Ukraine itself was one of the world’s leading producers of maize and barley, while Russia was a primary supplier of fertilizer and natural gas.

The report observes that when hostilities erupted, this fragile nexus of trade fell apart virtually overnight. Black Sea ports shut. Grain silos were leveled. Farmers could neither seed nor harvest in safety. Fuel prices skyrocketed. And in a matter of months, the shockwave permeated distant markets — from Egypt and Kenya to Bangladesh and Indonesia.

By mid-2023, the FAO Food Price Index had risen almost 30% above pre-war levels due to broad increases in cereal and cooking oil shortages. The worst hit were import-dependent nations, as the price of basics such as bread and rice increased to a level that was beyond the reach of most households.

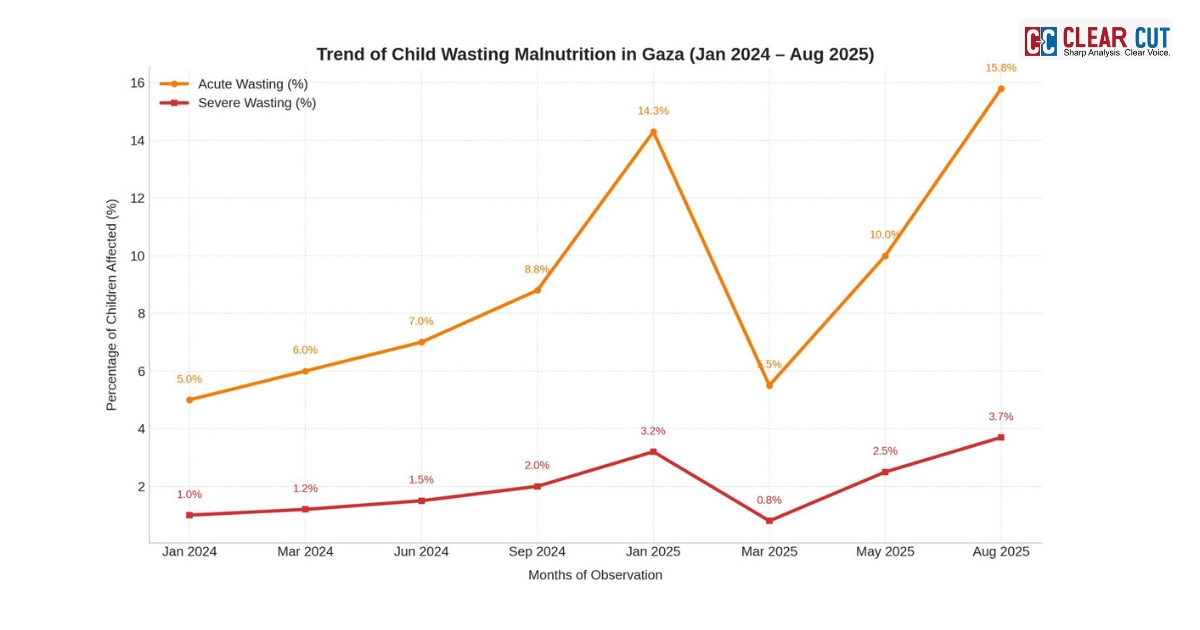

Dr. Sarwar and Rye explain that this “shock to global food systems” was not only economic. It was nutritional and social. Higher prices made families cut back on dietary diversity, switch to cheaper processed foods, or forgo meals entirely. In vulnerable areas, these changes are reflected in increasing levels of undernutrition, anaemia, and child stunting.

Photo Credit: abcnews.go.com

A Chain Reaction of Shortages

The review structures its findings in five interlinking domains:

food security, energy, critical materials, transport logistics, and finance.

They all flow into each other. For example, the energy crisis caused by Russian gas sanctions doubled the cost of fertilizers, which depend considerably on natural gas production. Developing country farmers could not afford to purchase fertilizer, cutting yields, which contributed to price increases again in 2024.

While the network of transport and logistics that transported grain and fertilizers was under pressure from the destruction of railways and ports. The back-up routes via Eastern Europe and the Black Sea were costly and time-consuming. Insurance premiums for cargo became extremely high.

The report accounts for this as a “multi-layered disruption” — a domino scenario where energy shortages trigger shortages of fertilizers, which reduces crop yields, which increases food prices, which intensifies hunger.

Who Suffers Most

According to the review, the consequences of this global chain reaction are far from equal. Wealthier nations have buffers — reserves, subsidies, and flexible trade routes. But poorer, import-dependent countries do not.

In some North African, South Asian, and Middle Eastern countries, governments were forced to make a decision between subsidies for food and the importation of fuel. The UN World Food Programme (WFP) cited that 282 million people in 2021 were experiencing acute food insecurity, increasing to 345 million in 2023.

Humanitarian corridors were created to resume small volumes of grain exports from Ukraine, although these were short-term solutions. After the agreements collapsed in mid-2024, exports declined once more, and the price volatility persisted.

Photo Credit: BBC

The New Shape of Resilience

And yet, in the midst of a crisis, there are flashes of resilience. A number of countries have begun diversifying sources of imports, creating regional grain stockpiles, and making investments in digital supply-chain tracking.

The report gives instances like the case of Egypt collaborating with India for the import of wheat and the European Union investing in infrastructure to effectively store and transport grain. A few African countries are looking to produce fertilizer locally in a bid to cut imports.

These answers, the writers claim, are redefining the way the world conceives of resilience. The war might have begun in Eastern Europe, but its implications are worldwide: that food systems should not rely on a handful of chokepoints or individual suppliers.

What Lies Ahead

The authors state that the Russia-Ukraine war has speeded up a long-simmering debate on food sovereignty — the ability of countries to produce, distribute, and consume food sustainably and fairly.

Dr. Sarwar and Rye warn that the ripple effects of the war will last longer than the war itself. Even if the war stops, the supply chains it threw into chaos will never go back to their previous forms. Some routes of trade have irrevocably changed. New relationships and farming tactics are already underway.

The report concludes on a sober note: world food security is only as resilient as its weakest link. When another region’s harvest is laid waste, some other region’s table remains bare.

In an age when hunger now travels across borders as freely as information, this study is not merely about economics. It is about compassion — a collective responsibility to make sure that no kid in Kyiv or Cairo ends up sleeping on an empty belly due to a war they never volunteered for.