Photo Credit: Climate Action Tracker

Clear Cut Climate Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Sep 15, 2025 02:30 IST

Written By: Antara Mrinal

India is at a pivotal moment in its climate journey. While many praise India’s development of renewable energy, new policies, and ambitious long-term commitments, new analysis has highlighted the difference between these policies and the styles of response that findings suggest would promote reaching the 1.5 °C target per the Paris Agreement. The national discussion at present consists of two main themes: India’s likely emissions profile under existing policies, and the critical question of climate finance: in particular, how much developed countries will make available, and how much India will need.

India’s Emissions Task: insufficient for 1.5 °C goals#

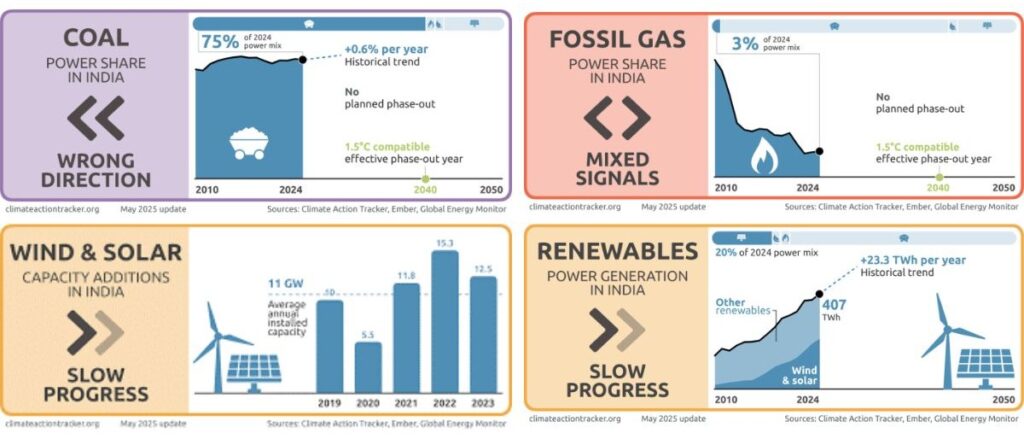

According to Climate Action Tracker (CAT), India’s current policies will likely result in emissions in the range of 4.0-4.3 GtCO₂e (Gigatonnes of Carbon Dioxide Equivalent), excluding land-use change emissions, by 2030. CAT ratings describe this emissions trajectory as “Insufficient” when compared to a fair contribution to limit India’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) contains a target of a reduction in emissions intensity of GDP of 45% from 2005 levels by 2030, a 50% non-fossil installed capacity in electrical power by 2030, and a 2.5-3 GtCO₂e improvement in carbon sinks from its forest cover and tree cover. But CAT’s analysis shows that, despite these targets, installed and expected policies and measures in India are aligned to a set of emissions outcomes that are not compatible with what is needed for 1.5 °C.

While one can see progress where renewable energy is growing; the share of coal in installed capacity has passed below 50%, and energy policies are evolving, the reductions in emissions that are required by 1.5 °C pathways remain significantly steeper. A CAT modelling scenario indicates that even very ambitious anticipated non-fossil capacity build-out (e.g. ≈500 GW) would likely be yielding approximately 3.8-3.9 GtCO₂e in 2030, if these assumptions were realised. So, unless there is a significant tightening of policy, phase-down of coal, decarbonisation of industry, and massive increases in provisions of support (both domestically and internationally), India will continue to be “Insufficient”.

The Climate Finance Obligation: USD 100 Billion and Counting#

Alongside the pathways of emissions, there is the question of finance. The Paris Agreement commitment made by developed nations to mobilize US$100 billion per year by 2020 in climate finance to support developing countries to achieve climate action and adaptation has been the focus of some climate finance work. 2022 was a significant year in this aspect: developed nations mobilized and provided approximately USD 115.9 billion to developing countries. However, this was two full years after the original commitment to mobilize this support by 2020.

For India, which has announced a target for net-zero of 2070, the issue of finance is not just about climate justice. It is about the capacity to deliver a conditional climate action plan that includes the eventual scale up of non-fossil fuel capacity, a phasing out of coal, and resilient infrastructure. Most importantly, it is about finding domestic and global climate finance. In the latest inter-governmental Climate Conference, India’s Environment Minister asserted the Global South issuing proposals of US$ 300 billion per year in finance by 2035 was encouraging; however, he concluded that developed nations’ historical emissions and moral obligation necessitates stronger, sooner, and more significant readiness to offer grant-based financing.

India’s need for funding to achieve net-zero by 2070 is significant: it has estimated that is may need just shy of USD 10 trillion in cumulative investment, supported by a study by Centre for Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) & its Centre for Energy Finance (CEF).

What “Insufficient” Really Means: Gaps & Implications#

Denoting the current policy of India “Insufficient” does not imply that none of these efforts are not valuable. It means that without stronger policy, deeper reductions in emissions, clearer trajectories, and collaboration (particularly related to finance and technology transfer), the country is likely to increase emissions consistent with 1.5 °C of warming.

The key gaps for India are:

- Continuing reliance on coal (especially older, inefficient plants that produce high emissions);

- Need to accelerate decarbonization of heavy industry (steel, cement, heavy manufacturing);

- Speed up clean mobility, energy efficiency, and renewables;

- Run robust adaptation and resilience planning (especially in climate-vulnerable areas).

Finance, Equity, and the Global Imperative#

India’s demand is clear: developed countries must meet their finance commitments, both in terms of the amount and in grants and concessional support and not -lending. India and others developing countries are already experiencing loss and damage from climate impacts, and the moral case for support is strong.

India is now advocating for “fair share” of finance and transparency on what is counted as climate finance, and stronger mechanisms to ensure the notion of climate justice for vulnerable communities through at G20 and other international spaces. The USD 100 billion goal was surpassed as an aggregate amount recently but this aggregates vagaries in terms of adaptation as opposed to mitigation finance, public versus private, and accessibility to small scale or remote-region-based projects.

Towards COP30 and Beyond: What India Can Do#

As COP30 (30th Conference of the Parties) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is approaching and here are some areas where India can sharpen its approach:

- Define and strengthen more ambitious 2030 targets focused on the most significant decreases in emissions (especially coal retirements, a cleaner industry, etc.).

- Strengthen policy levers to deliver on targets: carbon pricing, more stringent environmental standards, faster incentives for clean tech.

- Develop additional options for flexibility in renewables, energy storage, distributed clean energy, and incentive schemes.

- Advocate for clear, predictable, and grant-heavy international climate finance for developing countries, as well as improved access modalities.

- Engage regional initiatives for climate adaptation, risk sharing and building joint resilience plans (e.g., flood-prone Himalayan states).

Where India’s climate policies are evolving, “Insufficient” is a warning sign, not an assessment. To stay on a 1.5 °C compatible trajectory requires both national stated aims and global collective efforts. For India this means to take bolder actions, generate funding and deepen equity. Underpinning the countries policies is an underlying question: what is the fastest a country can grow without cooking the planet and how fairly can it be done so by those who are solely responsible and capable of doing so?

With inputs from:

- Climate Action Tracker (India policy & emissions projections)

- OECD (Climate Finance: USD 100B goal, public & private flows, developed countries)

- Times of India / Ministerial statements re: finance needs, summit proposals.