Photo Credit: Parinita Mathur

Clear Cut Education Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Sep 18, 2025 05:34 IST

Written By: Paresh Kumar

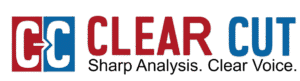

The central message of Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow is unsettling: much of what we call reason is intuition disguised as logic, and unless we recognize this, we will continue to stumble.

Published in 2011, this book is the distillation of Kahneman’s lifetime of research, much of it alongside Amos Tversky. Together they dismantled the myth of the rational human, and in doing so, founded behavioral economics. What Kahneman gives us here is not just theory but a field guide to our own biases.

He divides the mind into two systems. System 1 is fast, intuitive, automatic. System 2 is slow, deliberate, logical. The tension between the two explains why we survive in a complex world, but also why we misjudge risks, markets, and even each other.

The book is rich with anecdotes that expose the traps we fall into. Take the classic puzzle: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 (about ₹90) in total. The bat costs $1 (₹82) more than the ball. How much is the ball?” Most people instinctively answer “10 cents (₹8)”. It feels right. But it’s wrong. The correct answer is 5 cents (₹4). This is System 1 jumping ahead while System 2 stays lazy. Kahneman uses such examples to show that confidence and correctness often part ways.

Another powerful story is of judges in Israel reviewing parole applications. The data revealed a disturbing pattern: prisoners who appeared before the judge right after lunch had a 65% chance of release. Those appearing just before a meal had near zero chance. Justice was being served not by law but by glucose levels. A reminder that even experts are swayed by hidden factors.

Kahneman also introduces the anchoring effect. Ask one group if the tallest redwood tree is more or less than 1,200 feet, then guess the actual height. Ask another group if it is more or less than 180 feet, then guess. The first group’s estimates will be much higher. Our minds seize on the first number we see, even if it’s absurd, and use it as a reference point. In policy debates, budget forecasts, or even salary negotiations, anchors tilt outcomes silently.

Then comes the availability heuristic. Our tendency to judge frequency by how easily examples come to mind. People overestimate the risk of terrorist attacks but underestimate deaths from diabetes. Why? Because terror dominates headlines, while diabetes rarely does. This explains public pressure cycles: governments react to what is vivid, not always to what is common.

Perhaps the most policy-relevant insight is the framing effect. As Kahneman shows, people respond differently when told a treatment has a “90% survival rate” versus a “10% mortality rate.” The numbers are identical, but the frame changes decisions. For communicators, this lesson is gold. Whether it is vaccination campaigns, tax compliance, or climate messages, words shape choices as much as facts.

Kahneman also warns against the planning fallacy. Our chronic tendency to underestimate costs and timelines. His research showed that even when people knew projects usually run late, they still predicted their own would finish on time. Think of India’s metro lines, dams, or smart city projects, case studies in planning fallacies. Awareness of this bias, Kahneman suggests, should push us to use “reference class forecasting”: judging projects by outcomes of similar ventures, not optimism about our own.

The book closes with the poignant idea of the experiencing self versus the remembering self. The experiencing self lives in the present moment. The remembering self constructs stories. They don’t always agree. A vacation may be pleasant throughout but ruined in memory by a bad ending. Patients often rate painful medical procedures more tolerable if they ended gently, even if they lasted longer. Policy, Kahneman argues, often caters to the remembering self – healthcare systems, welfare programs, even tourism – all judged by recollection, not raw experience.

Why it matters today

In a world of instant news and snap judgments, we are ruled by System 1. Social media thrives on it. Elections are shaped by framing effects. Markets swing on availability bias. Governments make promises that fall to the planning fallacy. And experts, from doctors to CEOs, are no less prone to bias than ordinary citizens.

Kahneman’s book is not a cure but a mirror. It shows our limits, and urges humility. Awareness can help us design better policies, frame better communication, and pause before rushing to judgment.

Why everyone should read it

Because Thinking, Fast and Slow arms us with skepticism. Towards our instincts, towards confident predictions, towards neat stories. It is a reminder that doubt is not weakness, but wisdom. Policymakers will see why projects fail. Journalists will see why headlines mislead. Citizens will see why their own minds betray them.

We cannot switch off System

1. But we can train ourselves to know when to summon System

2. That discipline may be the closest we get to rationality. And that is why this book deserves a place on everyone’s shelf.