Photo Credit: Antara Mrinal

Clear Cut Climate Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Oct 11, 2025 11:25 IST

Written By: Antara Mrinal

In years when La Niña develops in the Pacific Ocean, India’s weather patterns are different: the southwest monsoon brings rainfall that is often average to above average for much of the country, but can also stall, cluster or return multiple times, resulting in longer wet seasons, and prolonged periods with higher humidity. The recent assessments of the Indian Meteorological Department’s monsoon forecasts show above-average cumulative rainfall is now a common feature of La Niña episodes, which is adding to flood risk in vulnerable basins and cities.

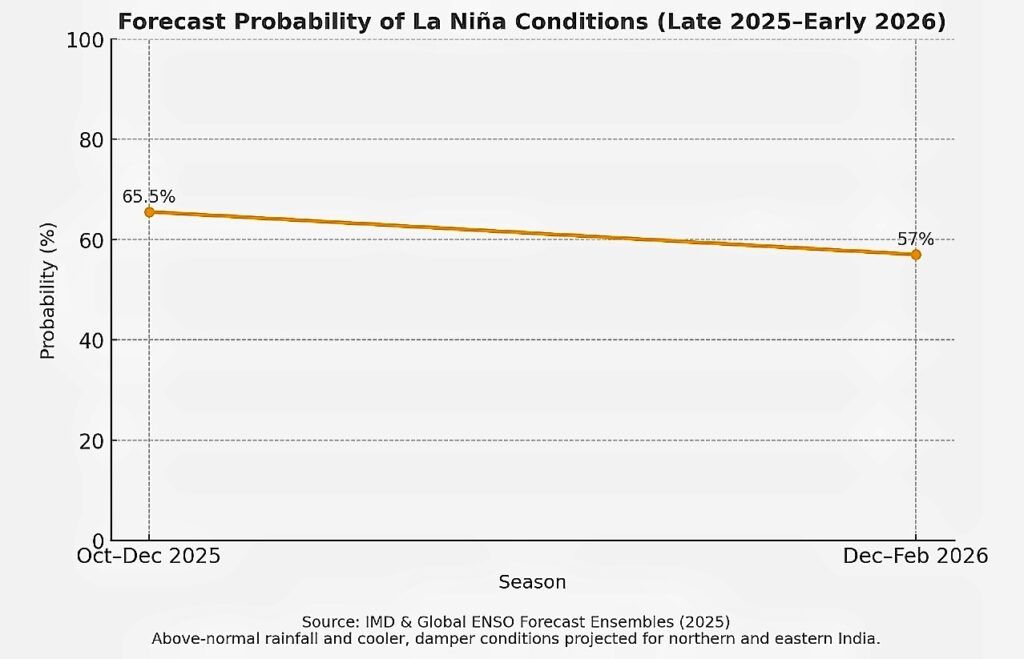

Climate monitors indicate a change from El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)-neutral state toward a La Niña state for the October-December 2025 season, with primary forecasting centers placing a clear (≈55-71%) probability that La Niña conditions will be evident in the ocean-atmosphere system through at least December 2025, likely into boreal winter (December-February). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI)/ Climate Prediction Center (CPC) model plume flag high chances of La Niña for October-December 2025, and largely similar probabilities are provided from other World Meteorological Organization (WMO) products. Operational monitors also describe this 2025 event as weak-to-moderate but likely to influence seasonal rainfall and temperature patterns across South Asia.

How La Niña in 2025 is Expected to Alter India’s Weather

Forecast ensemble models and recent Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) bulletins for late 2025 indicate an increased likelihood of above normal rainfall in several regions during the post-monsoon and early winter periods, and an inclination towards cooler, damper conditions over a large part of northern India compared to a neutral year. Operational IMD regional advisories in late-October – early-October 2025 also noted several heavy-rain events occurring in northeastern and eastern districts, reflecting the broader seasonal spatial change in conditions. Global ENSO forecasts indicate a ~60-71% chance of La Niña conditions for the Oct – Dec 2025 period and a ~54-60% chance of La Niña conditions to persist in Dec – Feb 2026. While these probabilities of ENSO are not sufficient to convince everyone, they are enough for health and disaster planners to consider the La Niña conditions a plausible near-term risk driver

Which People and Regions will be Most Affected

Population and health risk are at their highest where three factors overlap:

(1) Flood/waterlogging propensity (river basins, lowland plains and coastal belts),

(2) Population large enough to be rain-fed or informal (limited adaptive capacity), and

(3) Poor health, water, and sanitation systems.

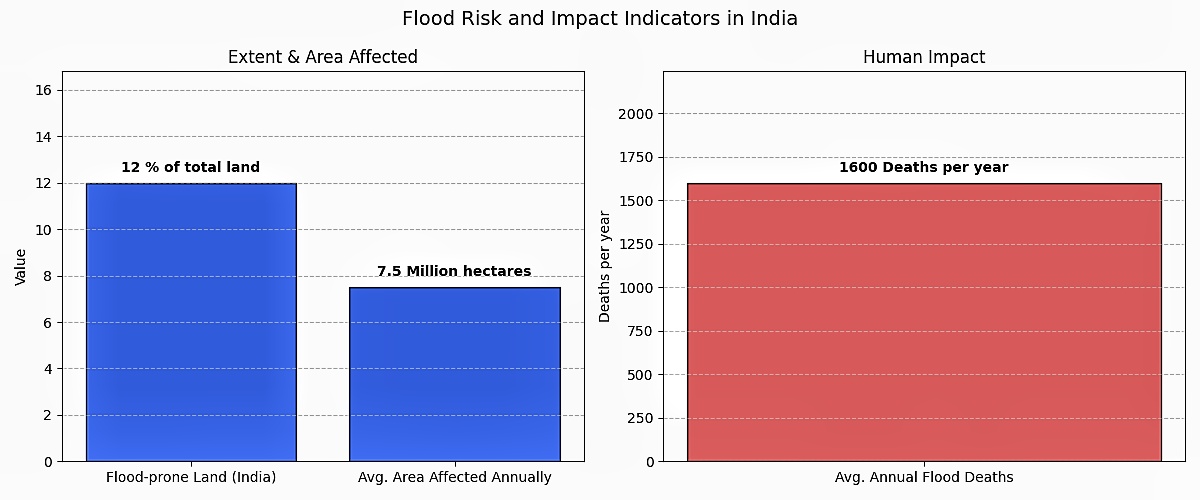

Vulnerability profiles from the Indian government and reports from the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) can yield information that roughly 12% of India’s area is flood prone, and on average historical reporting shows that about 7.5 million hectares (75 lakh ha) are flooded each year; flood events cause an average of ~ 1,600 deaths each year in historical reporting whilst also causing repeated losses in crops and livelihoods. States that experience recurrent floods made worse by the monsoon/La Niña season include Assam, Bihar, Odisha, West Bengal, parts of eastern Uttar Pradesh, coastal Andhra Pradesh/Telangana, coastal Karnataka and Kerala, as well as low-lying urban wards of delta and estuarine cities. Marginalised households (smallholder, landless and informal settlers, urban) are over-represented in these zones of high impact, and therefore have the most immediate health risks.

Health Risks Quantified

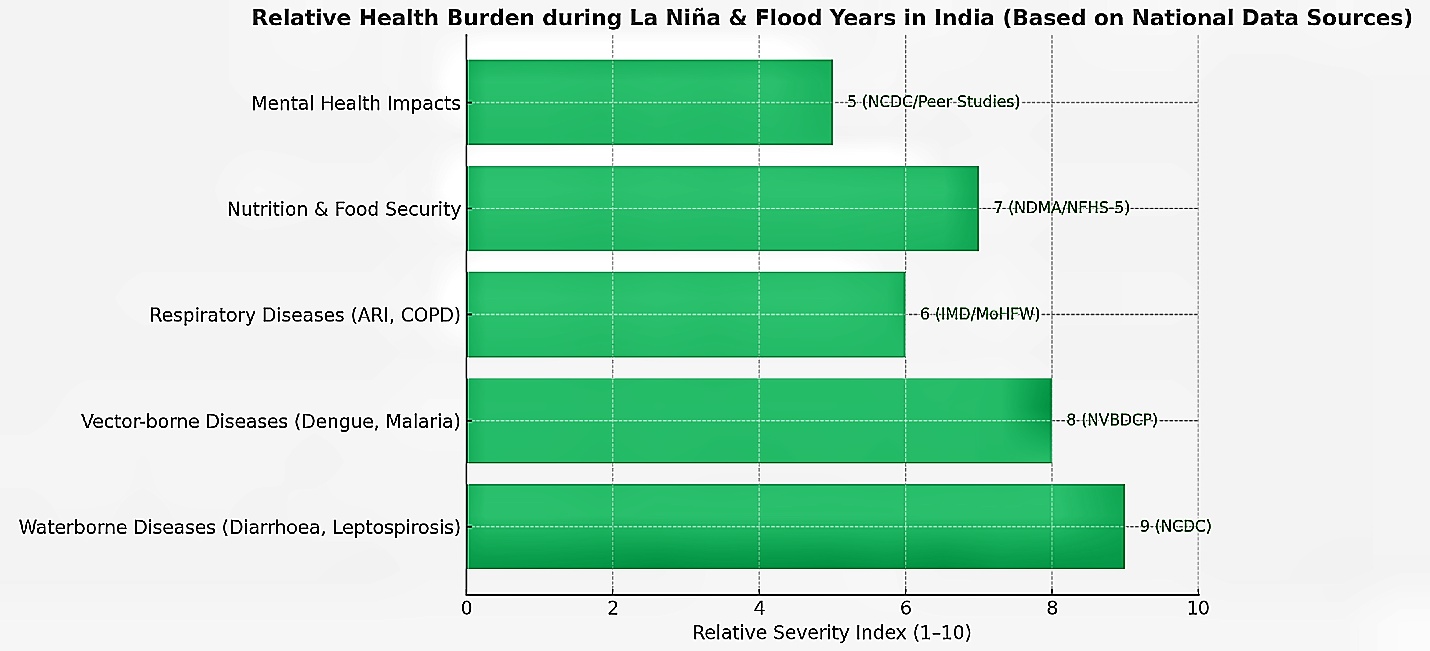

Waterborne diseases: As soon as the flooding occurs, the most significant signal of health risk is increased acute diarrheal disorders. A report by National Centre for Disease Control shows that in state outbreaks, acute diarrheal disease are the most commonly reported post-flood event; national surveillance and previous outbreak report from National Centre for Disease Control also show waterborne disease spikes after flood events consistently. Leptospirosis is underreported at the national level among post-flood disease, however it is noted as a possible significant risk where events occur in coastal and peri-urban settings, globally leptospirosis is estimated at ~1 million yearly worldwide with ~60,000 deaths, and in reviewing NDCP data there were repeated coastal outbreaks with wet years.

Vector borne diseases: Prolonged standing water or prolonged humidity will increase the potential for Anopheles breeding and increase opportunity for these vectors diseases to maximize transmission season, the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) reporting dengue tables and Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI) historical tables show a significant potential inter-annual diversity with some years with high rain coming with significant spikes.

Respiratory Disease: La Niña’s tendency to produce cooler, damper winters in northern India complicates health by potentially increasing respiratory infections in two ways; the most direct is that colder, humid conditions are conducive to virus spread and the second is that prolonged indoor crowding and damp housing leads to worse conditions for illnesses such as pneumonia and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Recent meteorological analyses and Indian reporting for La Niña and cooler winters observe significant increases in winter respiratory morbidity in 2024 and other La Niña years; health systems should anticipate some relative increase in ARI (acute respiratory infection) burdens among older adults and young children in Dec – Feb.

Nutrition and food security: Flooding and protracted monsoon events harm standing rabi and late kharif crops, disrupt supply chains and inflate local prices. Both NDMA and agricultural damage assessments following major monsoon floods demonstrate localized but acute food insecurity episodes; NFHS-5 baseline levels already demonstrate chronic vulnerability and high levels of stunting (35.5%) wasting (19.3%) and underweight (32.1%) among children under 5, signalling limited buffer capacity during events occurring during agricultural seasons. In practice, districts often see increased acute malnutrition case loads following consecutive crop shock or market shock.

Mental health: Empirical studies following floods in South Asia report sustained increases in anxiety, depression and PTSD in displaced households and farming communities. National mental-health surveillance data are sparse, but peer-reviewed and NCDC local assessments display clear burden of symptomatic burden which persist months following flood events, compounded by loss of livelihoods and housing.

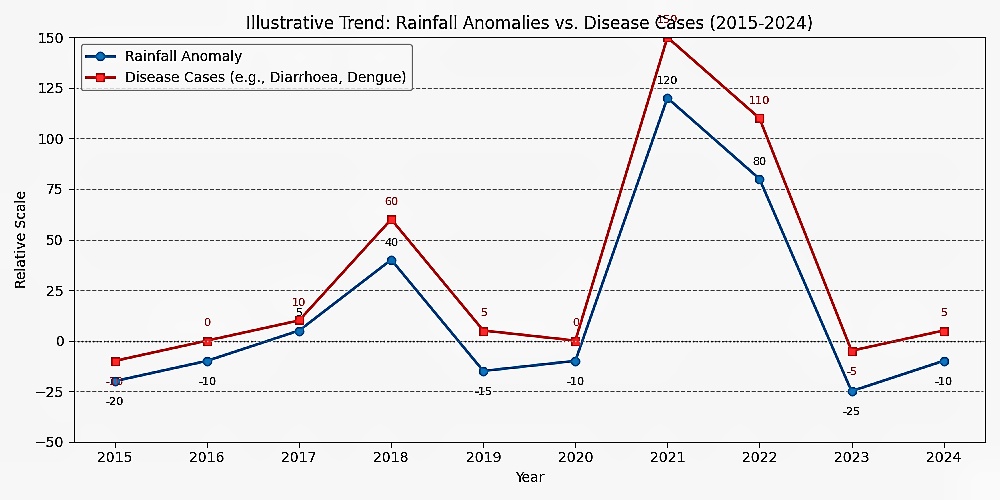

La Niña since The Last Decade

In the past ten years, strong La Niña or wet years (years that have a high rain amount) correspond to long-term and locally sustained increases in diarrhoeal diseases, dengue and other vector-borne diseases. National surveillance data demonstrate that, while absolute counts fluctuate (due to better diagnostics and reporting), the relative pattern is clear; wet or anomalously wet years yield spikes in water- and vector-borne disease and necessitate surges in emergency care. The main interpretive point for 2025 is that a weak La Niña, when accompanied by persistent local vulnerabilities (poor sanitation, high malnutrition baseline, informal housing), can have large local health impacts; thus, planners should treat 2025 probabilities as actionable alerts and not possible or distant possibilities. NVBDCP and NCDC historic tables (2015-2024) are the best available baselines for district accommodations/ comparisons to determine surge thresholds.

Early Action and Resilient Systems

The feasible preparedness actions supported by evidence at the state/district level include: pre-positioning oral rehydration salts (ORS), and antibiotics for diarrheal outbreaks in identified flood-prone districts, staging vector-control kits (larvicide, fogging machines, mosquito nets) before anticipated peak periods in the post-monsoon months, ensuring the continuity of nutrition supply chains for communities and take-home rations to avoid hunger-induced interruptions to feeding, ensuring continuity of antenatal services and immunization outreach for infants and children, in particular, through mobile teams, and scaling respiratory surveillance in the northern parts of India during December to February. Reviews and national disaster guidance have recommended anticipatory, meteorologically-triggered stockpiling and pre-deployment of community health workers (ASHAs/ANMs) into the highest-risk gram panchayats and wards, as identified from a NDMA hazard map maintained by the IMD. Operationally, NDMA and public-health agencies have consistently stressed the importance of initiating anticipatory action rather than simply reacting to an emergency, and several public health policy reviews have endorsed anticipatory actions, suggesting that they can reduce “caseloads” and speed recovery.

Sources (selected, primary datasets and official forecasts)

- NOAA / CPC ENSO Diagnostic Discussion (ENSO outlook, Oct–Dec 2025 probabilities

- IRI / Columbia ENSO plume (model ensemble probabilities for Oct–Dec 2025).

- WMO El Niño/La Niña updates (global producing centres consensus).

- India Meteorological Department (regional heavy-rain bulletins / monsoon assessments Oct 2025).

- NDMA flood vulnerability, annual averages and country risk profile.

- NVBDCP / MOHFW dengue and malaria surveillance pages and Malaria Annual Report 2024 (district-level program data).

- NCDC reviews on leptospirosis and post-flood infectious disease (surveillance guidance).

- NFHS-5 and recent analyses for child malnutrition baselines and vulnerability.