Photo Credit: Internet

Clear Cut Research Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Oct 07, 2025 11:11 IST

Written By: Janmojaya Barik

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Medicine recognizes the science of restraint and the art of balance.

Occasionally, the most compelling science stories are less about conquest and more about control. The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine recognizes such a tale, the one that plays out not in far-off galaxies or emerging technologies, but in our own bodies.

This year’s award has been presented to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their groundbreaking findings that reveal how the body’s immune system prevents itself from turning against the host. Their research on peripheral immune tolerance – a process that protects our defences from attacking the body’s own cells – has created new avenues for treating autoimmune diseases, enhancing organ transplantation, and developing cancer treatments.

The Body’s Balancing Act

Our immune system is a soldier and a judge. It needs to recognize and kill invading bacteria, viruses, or damaged cells, but also know when to stop. When this balance is dosrupted, the result can be devastating.

Autoimmune illnesses, such as type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, or multiple sclerosis, result when the body’s immune system gets confused and identifies the body’s own tissues as foreign invaders. The question that mystified scientists for a century was a simple yet deep one: why doesn’t it always do this?

In the 1990s, Shimon Sakaguchi in Japan discovered part of the answer. He described a unique subset of cells, known as regulatory T cells, which function as peace guardians in the immune system. Their function is to inhibit overreaction and avoid self-annihilation. It was a groundbreaking concept. Previously, it was assumed that immune tolerance, which was only generated in the thymus during the early stages of immune cell development was.the only type. Sakaguchi demonstrated that tolerance also occurs outside of this central organ ( in the periphery of the immune system) throughout life.

Photo Credit: nature.com

The Gene That Guards

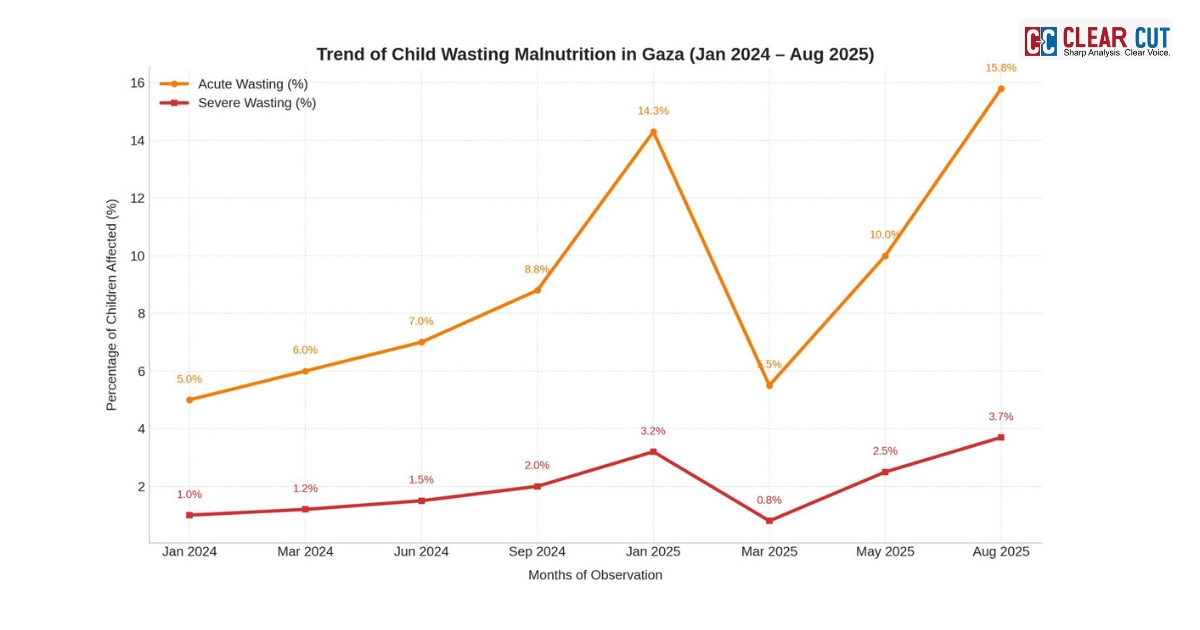

While Sakaguchi’s discovery revealed who performed this control, the next question was how. In 2001, Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell, working in the United States, identified the Foxp3 gene, a gene whose absence leads to catastrophic immune disorders. In mice, the mutation caused severe inflammation and early death. In humans, a faulty Foxp3 gene leads to a rare but deadly disease called IPEX syndrome, where the immune system relentlessly attacks multiple organs.

The research of Brunkow and Ramsdell revealed that Foxp3 is the master switch that determines regulatory T cells. Without it, they lose their identity and the immune system its restraint. When Sakaguchi later proved that Foxp3 was necessary for the function of his regulatory T cells, the puzzle pieces finally fell into place.

Their combined findings shed light on one of biology’s longest-running enigmas: how our immune system balances aggression with tolerance, protection with peace.

From Laboratory to Life

The consequences of this work extend far beyond scholarly fascination. Immune tolerance is already changing medicine.

In autoimmunity, treatments based on this work aim to restore regulatory T cell function, thereby educating the immune system to cease its assault on normal tissue. In organ transplantation, physicians want to induce tolerance so that the body will accept a new liver or kidney without ongoing reliance on immunosuppressive medication.

Perhaps most intriguingly, cancer scientists today investigate the other side of this discovery. Tumours tend to hijack the same mechanisms of tolerance in order to avoid immune attack. By carefully releasing these “brakes,” researchers are creating immunotherapies that unleash the immune system on cancer but do not harm the self.

What started as simple research on mice has evolved into a foundation for treating some of humankind’s most intractable diseases.

Photo Credit: Internet

A Lesson in Humility

The tale of the 2025 Nobel Prize is one of molecules or genes, not of arrogance. It teaches us that power without control can be devastating, whether in a civilisation or an immune cell.

Sakaguchi’s research was initially greeted with suspicion. His hypothesis that the immune system could govern itself by suppressor cells contradicted what was known. But he continued, sustained by meticulous observation and unobtrusive confidence. Brunkow and Ramsdell also toiled steadily to follow the genetic threads of tolerance, sometimes in the shadow of greater scientific news.

Their diligence revolutionized our knowledge of life itself.

Forgiveness, in a Biological Sense

The citation of the Nobel Assembly in 2025 refers to their research as a “milestone in understanding immune tolerance.” But maybe it is more lyrical than that. It demonstrates that even in our own bodies, forgiveness is necessary.

Just as humans must learn to live together despite conflict, our cells must live together despite friction. The immune system’s capacity to forgive our own tissues is not a weakness but a wisdom, developed through millions of years of evolution.

Looking Forward

The laureates’ findings have already started influencing the development of new medicine, such as treatments that will not only combat disease but also repair balance. Researchers are learning to increase regulatory T cells in patients to fix defective Foxp3 function and induce immune tolerance in transplants without compromising immunity altogether.

The research is intricate, but the vision is sharp: a future where curing equates to balance, not combat.

As the world cheers on the 2025 Nobel winners, their message resonates ever so quietly across all. Good health is not merely about defying. It is about understanding when to defend, when to change, and when to forgive.