Anyone who has worked in India’s development sector for a significant period will recognise a familiar pattern. Across states and districts, the landscape is crowded with organisations trying their best to solve difficult problems, yet most of them do so in isolation. The intent is strong, the commitment is real, but the way programmes are designed and implemented often creates parallel tracks of work that rarely meet. The consequence is visible on the ground: interventions that touch lives, but seldom transform them.

In many districts, whether in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand or Odisha, it is common to find several NGOs working in the same clusters of villages, each with a different mandate. One organisation may focus on maternal and child health; another may take up nutrition counselling through the Anganwadi system; a third may promote kitchen gardens and hygiene practices; a fourth may try to improve learning outcomes in government schools; a fifth may work on women’s collectives; and a sixth may run skill development courses for unemployed youth. Each programme has its own donor, targets, MIS, and field staff. To the outside world, this appears to be a vibrant ecosystem. But when you enter

the villages, the fragmentation becomes clear.

A household at the bottom of the economic ladder is often visited by multiple people from different organisations in the same month. One worker weighs the child; another checks the immunisation

card; another fills out a form on education; another asks about income; another Anyone who has worked in India’s invites the mother to an SHG meeting. Families try to cooperate, but the effort required from them is substantial. They answer similar questions repeatedly, attend meetings without understanding

how one initiative connects with another, and navigate a maze of advice, instructions and follow-up visits. They are not rejecting support; they are overwhelmed by its disorganised form.

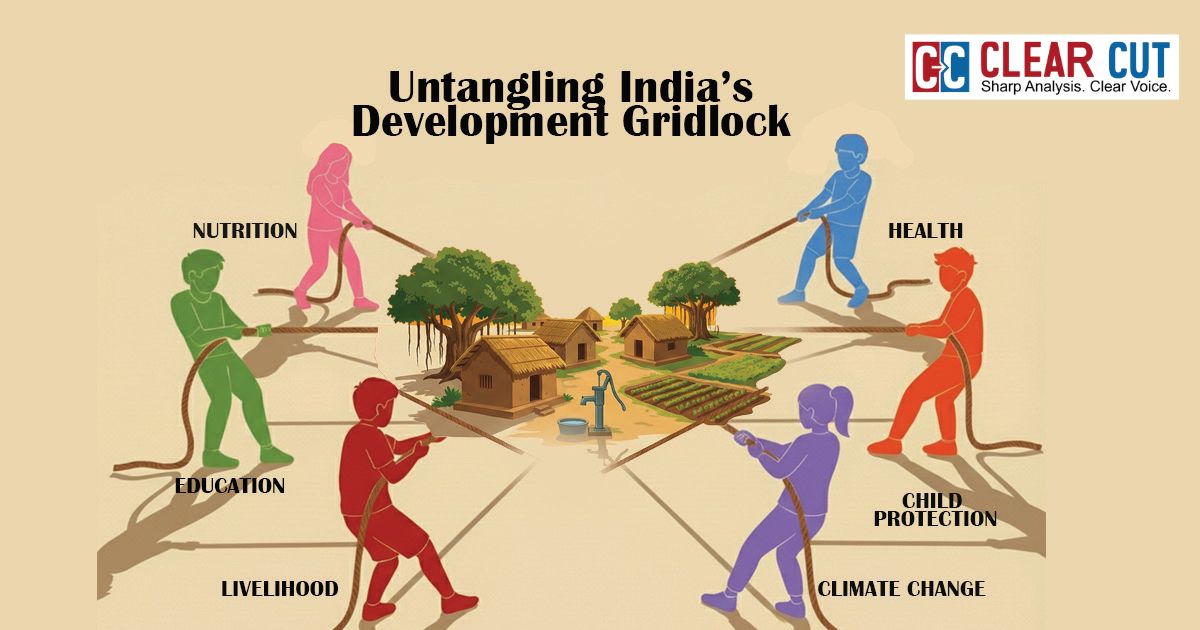

This is the core problem with silo-driven development. It is not that NGOs are doing the wrong things; they are simply doing the right things separately. A stunted child is not only a nutrition challenge. A school dropout is not only an education challenge. A family with low income is not only a livelihood challenge. These issues reinforce each other, and unless they are addressed together, the household continues to struggle. Development works as a chain. When one link is weak, the entire chain weakens.

The mismatch becomes even more evident when we evaluate outcomes. Organisations working in the same geography often claim overlapping success. If stunting reduces in a cluster, the nutrition programme may attribute it to dietary counselling, while the health team may credit deworming and antenatal care. A livelihood organisation may point to higher income, and a WASH programme may highlight access to toilets. The government, too, makes its case on the basis of improved service

delivery. The truth is that the change is collective. Yet, without convergence, measurement becomes a tug-of-war, and reports start resembling competing narratives rather than shared evidence.

The CSR ecosystem reflects a similar pattern. With annual CSR spending now exceeding .34,000 crore, India has the resources to drive long-term social change. But most CSR funds are spent in fragmented ways because proposals are designed sector-wise. One company supports anganwadis, another adopts a

school, a third funds a skill centre. All these efforts are helpful, but without alignment, they remain limited in scope. Imagine if several companies decided to jointly focus on one district for five years—with a unified roadmap covering health, nutrition, education, livelihoods and WASH. The combined impact would be far greater than isolated interventions spread thinly across geographies.

There are examples that show what is possible when organisations come together. In a district in Maharashtra, the administration brought a dozen NGOs to a common platform. Instead of protecting

their territories, they agreed to align their work around a shared set of villages and households. They developed a single household register, planned joint reviews and created one consolidated MIS. Each organisation retained its thematic strength, but the delivery became coordinated. Within a year and a

half, the district saw improvements across indicators—better nutrition outcomes, higher institutional deliveries, stronger learning levels and rising SHG incomes. None of this required new funding; it

required new behaviour.

The question, then, is not whether convergence works. The question is how to make it more common. District administrations can play an important bridging role by convening NGOs at regular intervals, mapping their areas of work and encouraging shared plans. Donors and CSR heads can redesign the way they fund programmes by including partnership requirements in their grants. NGOs themselves can look beyond organisational boundaries and recognise that their success is tied to the success of others working on complementary issues. The idea is not to dilute specialisation, but to strengthen it through coordination.

A simple step such as maintaining a common household register can transform the way programmes function. If every organisation working in a village updates the same record such as, basic demographics, maternal health status, child nutrition, schooling, livelihood sources, SHG participation, then everyone

gains a fuller picture of the household’s needs. The data becomes a shared foundation for action, not a proprietary asset.

Another important shift is the creation of multi-tasked community cadres. Instead of ten workers from ten programmes visiting the same family, a single local resource person can serve as the first point of contact. This approach reduces family fatigue, builds trust, and ensures that conversations about health, education, nutrition and livelihoods happen together rather than in fragments into baselines and endline evaluations are equally critical. When organisations agree to measure outcomes through common tools and sampling frames, the results reflect the collective contribution rather than fragmented claims. This helps donors see the true value of convergence and encourages them to support integrated models.

Ultimately, development is about people, not projects. The families we work with do not experience life sector-wise. They do not separate health from income, or nutrition from education. Their challenges

are layered and interconnected. Our programmes need to reflect that reality.

Collaboration is not about giving up identity; it is about amplifying impact. It helps NGOs do what they already do, but with greater depth and reach. It helps CSR create meaningful, measurable change. It helps government systems function more effectively. Most importantly, it helps households experience support in a way that feels coherent, respectful and useful.

India does not lack resources, institutions or intent. What we lack is coordination. If the development sector can shift from competition to convergence, we can move from scattered improvements to genuine

transformation—village by village, household by household.

The time for silos has passed. The time for working together has arrived. And the communities we serve deserve nothing less.

Clear Cut Livelihood Desk

New Delhi, UPDATED: Jan 23, 2026 09 :00 IST

Written By: Paresh Kumar